Approaching a full year of telling stories about the neighborhood alongside my colleagues, I’m humbled by the way our team has shown the world this pocket of Los Angeles. From “A Mango Tree Grows in Virgil Village,” to a “Love Letter to Los Angeles,” it’s clear that each of us harbors a deep and unshakable connection to this place we call home. It’s also true that we’ve still got far more stories to uncover together. Take my decade-long affinity for a piece of Silver Lake, hitherto unknown in print, to name one example.

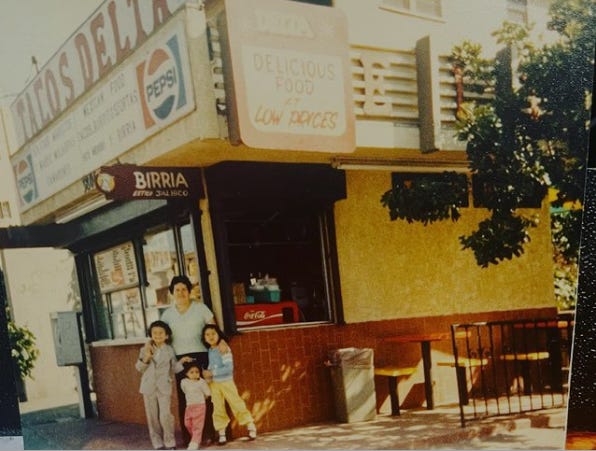

One of my favorite places to grab a quick bite is at Tacos Delta, a family-owned restaurant near Sunset Boulevard and Lucile Avenue operating since 1981 (and just a stone’s throw from the historic Black Cat). I swear by the fish tacos there, but growing up, between my friends and I, admitting fondness for much of anything from Silver Lake was a no-no for the way much of the neighborhood encompassed “high-maintenance” we largely deemed bizarre and out of touch; it wasn’t cool to have money, after all. It wasn’t anything. Instead, hole-in-the-walls like Korner Grill, once across the street from King Middle School, were our go-tos. The reason for this was simple. Their delicious chili cheese fries sold at less than $3.00. (Today, the site where Korner Grill stood is under massive redevelopment, presumably for more market-rate apartment units).

A lifetime since “growing up,” however, with the endless reach of the online world, poets and storytellers like Yesika Salgado also describe slices of a more relatable, or “...pre-gentrification Silver Lake…” that few of us–natives included–even knew existed. In doing so, Salgado uplifts what I’d call “other Korner Grills,” or pieces of working-class culture tucked humbly inside of the city’s trendiest localities, including for audiences in broader L.A., but also for neighbors like me and my friends on “that other side” of Hoover street.

“Black Identity Trapeze Artist” Rhys Langston similarly tells stories about “the old neighborhood” that even unsuspecting “experts” here might still be surprised by, like about his “Single Black mother renting a two bedroom in Los Feliz…[and he and his] brother not realizing that was a zenith.” In 2017, Lansgton dubbed himself “Jesus of Los Feliz,” because what’s more L.A. than this kind of self-invention from a half-Black, half-Jewish artist? His notes on the versatility of sounds at Barnsdall Arts Park from his latest album, Grapefruit Radio, also certify his familiarity with an often unseen or unheard Los Angeles (Side-note: I’m interviewing Langston for my podcast this Thursday evening on Instagram, in case you’d like to hear more).

But what’s the purpose of these stories, or one might say, anecdotes, anyway? Maybe it’s fair to call poems and articles about these lands we’re connected to just “passion projects,” or simple “outlets” for what we consider unique about our living–or having lived–here. Or maybe the stories they trace together actually form reflections for us to see ourselves and each other in ways that transcend time and space.

In her 2022 book A Place at the Nayarit, USC Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity Natalia Molina describes the lengths actually covered by her grandmother’s Nayarit restaurant in Echo Park, which her family officially held in the neighborhood from 1951 - 1976. In addition to supporting generations of workers from across the way with jobs, the restaurant also supported Grandma’s hometown newspaper, El Eco, “[which] functioned to help keep the community together, even as it was spread over thousands of miles...Every Nayarita family [or people from the Mexican state of Nayarit] in Los Angeles that I knew when I was growing up [in Echo Park] subscribed to El Eco but not necessarily to La Opinion.” This is because the latter, Molina explains, covered Mexican-American culture in the city at large, while people from Nayarit sought something far closer to home. It was hardly a question, then. Nayaritas in both L.A. and Mexico paid for subscriptions to El Eco to keep up with each other.

Molina’s observations also remind us that long before Instagram stories updated us on the latest goings-ons, small and local newspapers published stories about friends and family to both recognize and humanize scores of people “making a neighborhood” in lands as new and uncharted for them as Los Angeles.

Not so differently, today the market is as uncertain as ever for the city’s working-class families, small businesses, and those of us who rely on the belonging they help us maintain. It’s also a precarious time for news and other publications covering L.A. culture. But like those Nayaritas who supported El Eco over decades to stay connected with their loved ones despite vast distances, today we support each other’s independent storytelling because our stories can and consistently do challenge the gentrification pressuring our communities.

As we approach a full year of Making a Neighborhood, then, and two years since our landmark storytelling collaboration through Redlining, Gentrification and Housing in East Hollywood, I seek to not just maintain our work together, but to grow its reach and list of supporters; something tells me that doing so can light a path for our communities, open new doors for ourselves and others, and much more.

J.T.