J-Flats: Stories From a Redlined Neighborhood

"For a community to survive, it needs people who are going to be curious about who was there before"

In 2021, as part of our extensive, multimedia project “Making Our Neighborhood: Redlining, Gentrification, and Housing in East Hollywood.” J.T. and I (Samanta Helou Hernandez) published a 100-page magazine about these issues. The magazine, which sold out within two months, was a result of years' worth of work in the neighborhood. This September, we’re sharing four essays from the magazine for readers who didn’t get a chance to buy a copy.

THE ALBRIGHTS — 1892

George W. Albright was born enslaved in Mississippi in 1846. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Albright became a secret runner in the Lincoln League, informing enslaved people that they were free.

“The slaves, themselves, had to carry the news to one another. That was my first job in the fight for the rights of my people—to tell the slaves that they were free, to keep them informed and in readiness to assist the Union armies whenever the opportunity came,” said Albright in an excerpt from a 1937 interview with the Daily Worker.

Albright went on to serve four years in the Mississippi Senate.

“I helped to organize the Negro volunteer militia, which was needed to keep the common people on top and fight off the organized attacks of the landlords and former slave owners. We drilled frequently – and how the rich folks hated to see us, armed and ready to defend ourselves and our elected government!”

He also taught at the first public school in Mississippi and met Josephine Hardy, a white teacher from Massachusetts, who taught freed people. Albright and Hardy moved to Los Angeles in 1892, arriving by train on Christmas Eve. They settled in what is now North Westmoreland Avenue, south of Virgil Village in East Hollywood. At the time, the area was all farmland, full of fruit orchards and streams. The Albrights homesteaded the area, living off of the land and the grist mill George ran.

The Albrights witnessed their neighborhood change from farmland to city blocks, evolving into a Japanese-American enclave. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren all grew up on North Westmoreland Avenue, attended Dayton Heights Elementary school, and forged close friendships with their Japanese-American neighbors.

THE MARSHALLS

Crystal Albright, daughter of Josephine and George, was born in 1889. She married Rufus Marshall and built a house with him on North Westmoreland Avenue, just north of her parents’ original homestead. Crystal, known for her excellent cooking, started a catering business with her husband, which they ran until she retired in the 1960s.

In her later years, Crystal Marshall told stories of her father, George Albright, catching trout for dinner on Madison Avenue. She wrote of the early years in the neighborhood:

“In the spring and summer, wild flowers grew in profusion, rabbits and quail were plentiful and along the streams there was good fishing. Marshy ponds surrounded by tules and tall cattails were the landing places of wild duck and geese as they migrated north and south. It was a beautiful sight to see the formation of stately geese as they came in for a landing.”

The Marshalls were close to their Japanese-American neighbors, particularly the Hoshizakis and the Kakibas, who lived on either side of them. Their daughter, Barbara Marshall, remembers food and culture being exchanged over the hedges of their houses":

“My mother and father ran a cafeteria at the library in downtown Los Angeles. A lot of times, we would have things left over and would pass them over to the Kakibas and the Hoshizakis. Before we knew it, we would get Japanese food from the neighboring families.”

In 1942, when the Japanese-Americans were forced to leave for internment camps, The Marshall family helped their neighbors by storing items for them, visiting them at the Pomona Assembly Center, and looking out for their properties.

“I remember it was such a dismal day when they had to leave,” says Barbara Marshall. “My father would drive the different families up to Santa Monica Blvd where the buses were picking up and sending off the people [Japanese Americans] in the neighborhood. In the meantime my mother was cooking, giving them breakfast, making biscuits.”

Barbara Marshall, daughter of Crystal and Rufus Marshall and granddaughter of George and Josephine Albright, was born in 1927. Like her mother, she also grew up on North Westmoreland Avenue in the Dayton Heights area, which by that time, had become a Japanese-American enclave nicknamed “J-Flats.”

Barbara developed close friendships with her Japanese-American neighbors.

“I fell in love with Japanese food. We could walk over to the corner market where Mr. Hoshizaki had the grocery store and we could go in there and buy goodies. Behind the Kakibas’ house, there was a gym and the men would go there for judo and we would watch from our house.

I didn't know we were in an integrated neighborhood until I learned about that word. To be able to walk down the street without fear of people calling you names because everybody was part of the neighborhood.

I felt comfortable in my neighborhood and with my friends, the Hoshizakis on one side and the Kakibas on the other side. It was like family. That’s why it was so devastating when the war came and they were taken away from us.”

Barbara was starting Japanese classes at the language school in the neighborhood when the war broke out, and soon after Japanese-Americans across the West Coast were sent to concentration camps.

Barbara and her mother visited their neighbors, the Hoshizakis, at the Pomona Assembly Center, where they were held for months before being sent to an internment camp in Wyoming. Barbara’s mother brought food and apple pie for young Takashi and Kyoko Hoshizaki.

“I can remember being in tears leaving my friends,” she remembers. “When I graduated from high school is when the Japanese were just coming back.”

Barbara Marshall went on to work in the alteration department at Saks Fifth Avenue. She eventually moved to Monrovia, where she still lives to this day.

KAREN BURCH: THE GRIOT

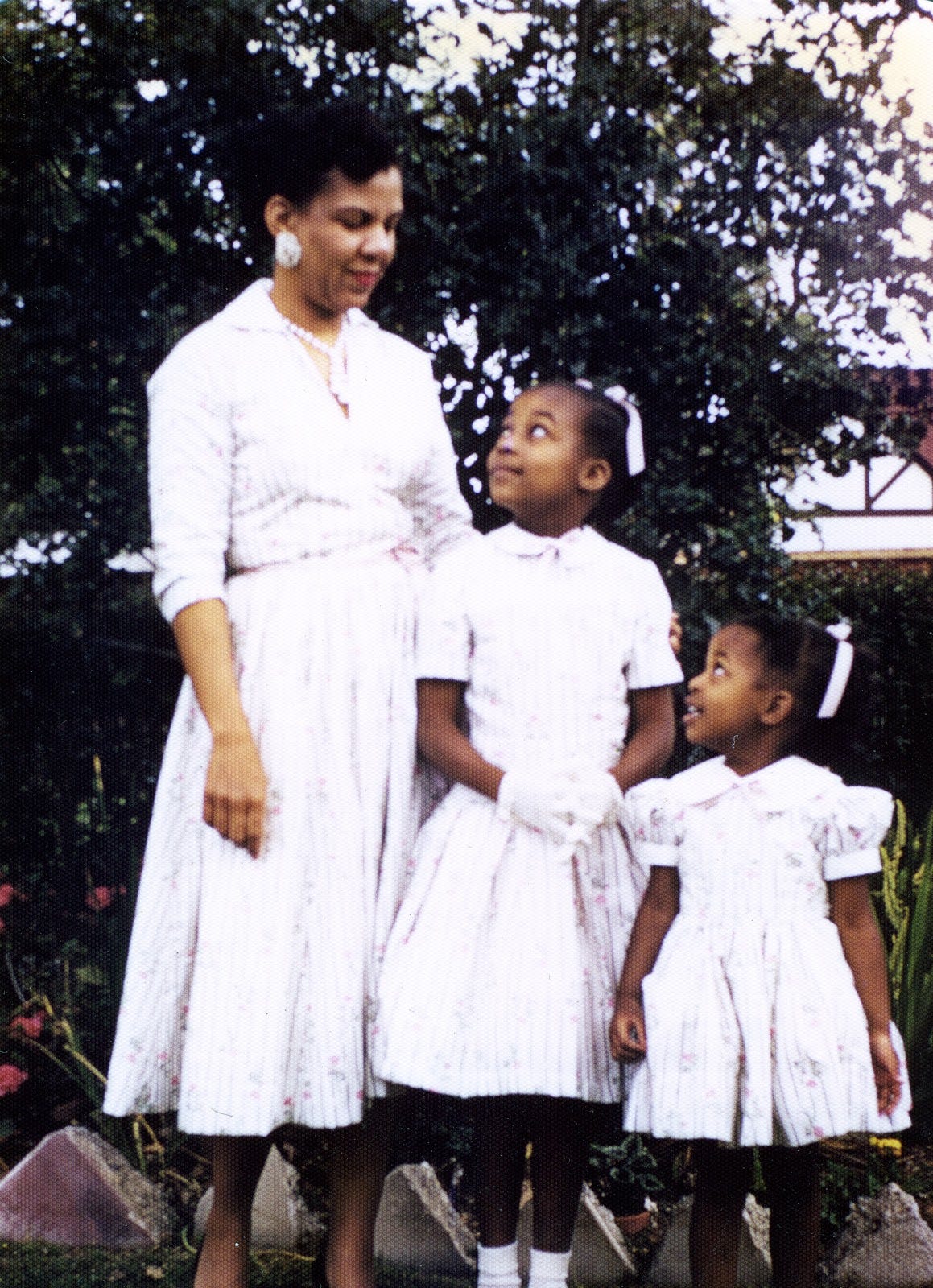

Karen Burch is the granddaughter of Crystal Albright Marshall and great-granddaughter of Josephine and George Albright. She was born in 1952 and grew up in the Dayton Heights area on the same lot as her great-grandparents' original homestead.

“My great grandmother had very close friends in the Japanese families, as did my grandmother. My mother, my aunt, and my uncle, their best friends, were Japanese. When the three of us came along, all of our best friends were Japanese. It’s always been that way. Basically all of us went to school together, church, girl scouts. We were all intertwined in each other's lives for generations.

I used to love going to my friend Christine’s house after school. Her mother would either have bologna sandwiches or she would have sushi, both of which I loved tremendously.

One of the Black traditions around New Year’s, you make black eyed peas and they’re a symbol of good luck and prosperity for the new year. When my mom would make them, they were shared between households.

During Christmas, we would sing the carols in both English & Japanese. In the regular church service when we were older, the pastors would do part of their service in Japanese & then do it again in English. I just remember loving to hear the language.

My grandmother would talk about how my great-grandmother [Josephine Albright] and the Japanese obasans, the grandmothers, would sit on the porch and get stuff ready for the evening meal. In that generation, they couldn’t speak the same language, but they spoke the language of friendship.

The day the Japanese had to leave the neighborhood, they were limited to one or two suitcases apiece, and that’s all they could bring. There were one or two families who asked my family to take power of attorney over their property and bank accounts.

The Kakibas had a collection of silk Kimonos. They left a trunk of things like that with my grandparents. My grandparents kept the articles safe.”

“I was raised at 537 North Westmoreland Avenue. When I was eight years old, my parents wanted to build a house on the lot because the old house was almost 100 years old. They found a house near CBS studios. In that area, there are these precious Spanish houses. There was a company that used to take a house in one place, dig out the foundation, lift it up, and move the whole house in its entirety to a new place.

Mom went to UCLA and got her teaching credential in home economics. There were a group of them who were hired as teachers in LA Unified [LAUSD], and they were among the first Black teachers.

When she got her masters, she pursued a career path as counselor, and then as head counselor at LAUSD in South Central. She started a reading program that began with students in the third grade. Then she would take the juniors and seniors on field trips to universities so that young Black children could get a taste of higher education.

When I was little, we could go outside and not come home until lunch or dinnertime and we were always somewhere in the neighborhood, exploring. There wasn’t the concern over kids getting into problems.

I was looking at the photo of my sixth grade graduating class, and it’s like the United Nations.”

Crystal Albright Marshall, Karen’s grandmother, wrote about the neighborhood in the 70s:

“In the Dayton Heights School which is the center of the community life in the neighborhood, you will find almost a League of Nations. Children from many European countries, as well as those from Japan, China, the Philippines, and the islands of the Pacific along with Caucasian and Negro children, all go to school happily together.”

“I left the neighborhood at eighteen in 1970 when I went to UCLA. I didn't move back to the neighborhood until my grandmother died in 1990. When I came back, there was a big change, there were a lot more Hispanic families. I'm the only one that came back to the neighborhood. In the last five or ten years after the turn of this century, I started to see a lot of hipsters moving in.

When I moved into my second apartment, my mom came to stay with me because she was bed ridden at that point. She sold her house, the original homestead, some time around 2005. When she sold that, it was the last of our ownership in that little area.

It’s been very sad for all of us—especially for me because I lived there—not to be able to have at least one of those properties still in the family to be able to pass it down.

Rents go up three percent every year. The three percent adds up over time. Suddenly, I was in a range where I couldn't sustain it. I left in 2019. I got priced out of the neighborhood.

It was a terrible feeling saying goodbye, first to the people, the family members over the years, then to the houses themselves, and now to the neighborhood.

For a community to survive, it needs people who are going to be curious about who was there before and to be invested in it.

I think about my grandmother living through the first car, the first airplane, in the 60s, seeing a man walk on the surface of the moon. These things happen slowly until all of a sudden you notice that there has been change.

I always laugh when people say. ‘LA has no neighborhoods and no history.”

Following in her mother’s footsteps, Karen worked for ten years as a school psychologist at LAUSD. She later became a writer and producer in multimedia, and returned to psychology before having to medically retire following an injury. She is the keeper of her family’s story and is currently working on a book about her family history in Los Angeles.

Karen turns 70 at the end of this month and her niece is currently fundraising for her birthday to support her as she continues working on her book.

Archival images courtesy of Karen “Kiwi” Burch and the Albright-Marshall family. All other photos by Samanta Helou Hernandez.

FYI - Origin of J-Flats many folks thought the J meant Japanese, Japanese Flats but it not, during the late 1950’s the neighborhood’s Asian street gang was called the Black Juans consisting of Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans teenagers many of them living on J uanita Ave. The gang broke up early 1960’s due to a gang fight and shooting with another eastside Japanese gang at Shatto Park

What an amazing story- history- THANK YOU