J-Flats: Stories From a Redlined Neighborhood Part 2

"It was one of the few places people could move into because it was restricted."

In 2021, as part of our extensive, multimedia project “Making Our Neighborhood: Redlining, Gentrification, and Housing in East Hollywood.” J.T. and I (Samanta Helou Hernandez) published a 100-page magazine about these issues. The magazine, which sold out within two months, was a result of years' worth of work in the neighborhood. This September, we’re sharing four essays from the magazine for readers who didn’t get a chance to buy a copy.

THE HOSHIZAKIS

Takashi Hoshizaki was born in 1925. His father, a college graduate in Japan, migrated to the United States to work for his brother’s mutual trading company in Little Tokyo. As the Immigration Act of 1924—which banned most migration from Asia—was about to pass, Takashi’s travelled to Japan and got married to a woman who would become Takashi’s mother. They made it back to Los Angeles before the exclusion act went into effect.

In 1932, Takashi’s father decided to strike out on his own and moved the family to the Dayton Heights/Virgil area, by then already known as “J-flats.” He opened Fujiya, a Japanese grocery store on the corner of Virgil and Clinton. The Hoshizakis lived behind the grocery store until Takashi’s dad had enough money to buy a property (in an American-citizens’s name) on North Westmoreland Avenue right next to the Marshalls. The two families would go on to be close friends.

“Dad mostly sold Japanese goods. We had 100 pound sacks of rice that were sold. We sold a lot of shoyu. My dad had a delivery service too.”

“Growing up, we had quite a number of different ethnic groups. It was nice. We had a good mix of people toward the end of the 30s. We had the Marshalls, who were Black family. Down at the other end of the block, we had the Torrez’s who were Mexican. We also had Filipinos and also white families.

It was one of the few places people could move into because it was restricted. It was much later on as an adult that I realized we were restricted in East Hollywood where all the minority people were able to rent apartments and run businesses.

As a youngster, the streets were completely open. I still live in the same area today. I go out and think back, when I was a kid there wasn't a single car parked along the street, which in turn made it kind of nice as a youngster because we could play football or baseball out in the street. I remember taking the streetcar to go to Belmont High School.

Crystal Albright Marshall, nana we called her, mentioned that when she was a youngster at about the turn of 1900s, her dad used to go to Madison Avenue and catch trout for dinner. By the time I arrived 30 years later, that whole place was paved over. It's neat to think back about the geology and how the city covered everything up.”

In 1942, less than a year after WWII broke out, Takashi’s family, along with his Japanese-American neighbors, were forced to leave behind their homes, properties, and businesses to be sent to concentration camps across the U.S. Takashi’s family was first sent to the Pomona Assembly Center, also known as the L.A. Fairgrounds, where they stayed for nearly four months before taking a train to the internment camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

“I realized we would probably be forced to leave as different restrictions were being placed, we had the curfew and then we had a 5 mile travel limit. We were closed in. Looking back at history, it’s the step by step way of moving people around and I think of what happened in Nazi Germany and you see the same pattern.

We left in May of 1942. I was 16. We had no idea what was going to happen to us. By that time I guess we were all psychologically confining ourselves.

We gathered at Hollywood Independent Church and the buses came and took us to Pomona Assembly Center.

While I was there, they told me I had visitors. Nana [Crystal Marshall] was there, she had baked an apple pie. There was a way of cooking an apple pie so the crust would stand up and there would be separation between the apples and crust, she then scooped in vanilla ice cream between the apple and crust. So I had pie a la mode passed through the fence. She would do things like that for us.

The Marshalls were very supportive in keeping an eye on our property while we were gone.

In August 1942, we boarded a train. We were on the train for about three days. We ended up in Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

Most of the farming families lost everything. I got pretty angry thinking about that. I began to think that it was all wrong, that we were sent into these camps. The government illegally took everything away from us. In 1944, when the draft notice came, I had made up my mind that I would not go into the army until all these wrongs were corrected. I refused to go to the physical exam.

We thought we could use resisting the draft as a means of going to the courts to contest the internment. But we were found guilty of draft evasion. I was arrested along with 63 other men. We ended up with a three year sentence. I served two years at McNeil Island federal penitentiary.”

“In prison we had people from all different levels. We had bankers, lawyers, then we had people from the ghettos. It was a whole range of individuals. In our spare time, some of them would sit with me and we would talk about our experiences. I got a real feeling of what was happening to the Black people.

I had just turned 18 when they wanted to draft me. I got out of prison when I was 20 years old.

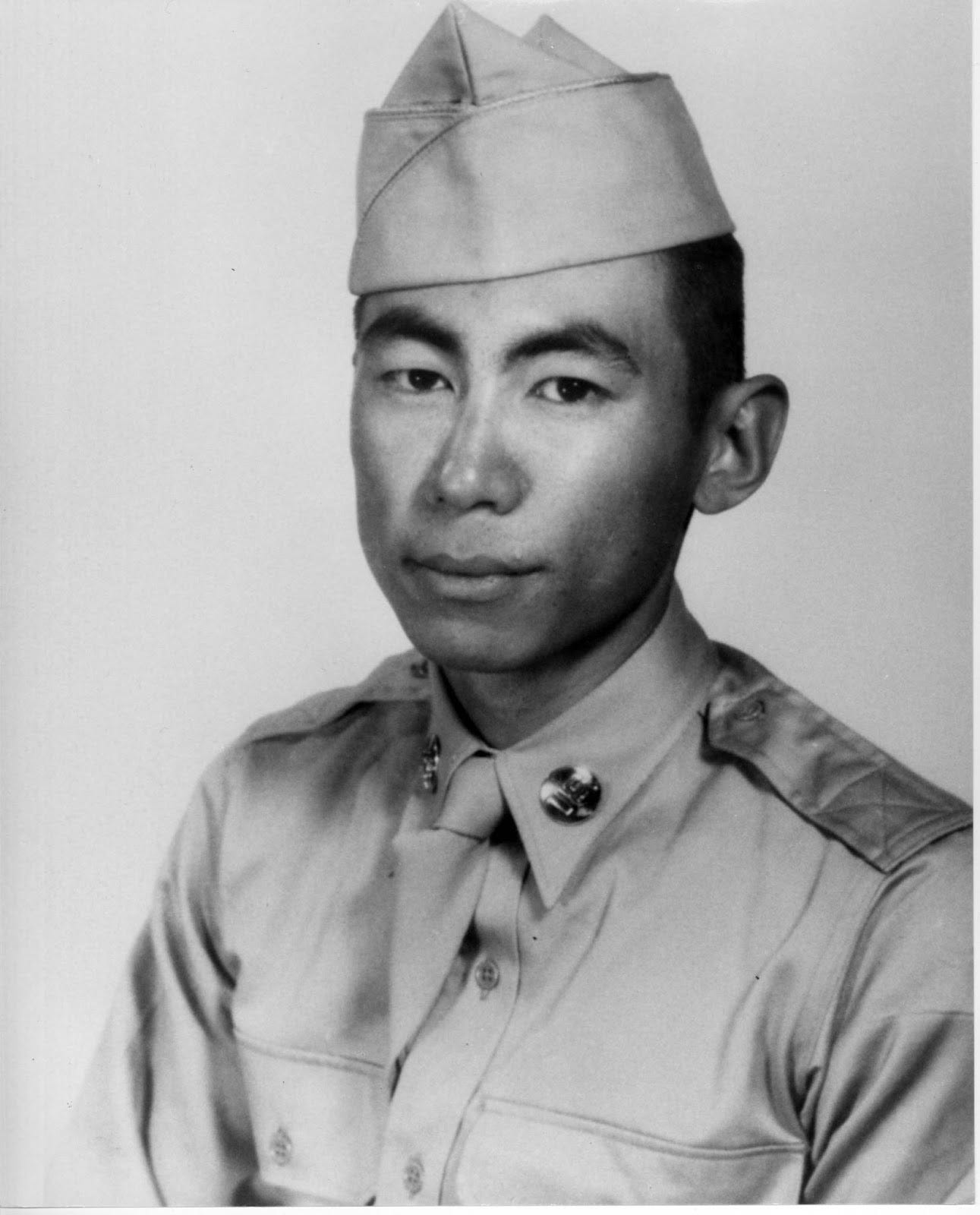

About a year later in 1947, the mass resisters got a presidential pardon from Truman. Then the Korean War started. I got my second draft notice. By then, we had our civil rights back and the family was back home, so I gladly served in the army as a medic at Fort Hood for two years.”

“Before the war, in our neighborhood, most of the people were renting, so when they had to leave, they lost quite a bit financially. We were fortunate because my dad leased out the house so we didn't lose any of the items we had left behind.

Going into the nursery business was an opportune situation because during the war years no one really took care of the lawns or the landscaping. After the war ended there was a huge demand to bring everything back to what it was before. Before the war, most of the gardening in California was done by the Japanese.”

In the time between being released from prison and getting his second draft notice during the Korean War, Takashi met his wife Barbara at LACC, a Chinese-American also studying botany. Takashi went on to receive his masters at UCLA, and later a PHD in botanical sciences.

“I went into botany because my family had a nursery. I was interested in what happens to astronauts who have 90 min days instead of 24 hour days. NASA funded most of my research. I was using plants to look at circadian rhythms.”

Takashi worked at the Jet Propulsion Lab for many years. His late wife became the leading expert on botanical ferns and travelled the world studying the plants. They had two children, John and Carol.

Takashi, now 96, still lives on North Westmoreland Avenue in a house full of exotic plants and jarred ferns. He is a board member of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and continues to share the story of what happened to Japanese-Americans during WWII so it’s never forgotten.

“Today we have the Latinos coming in and they're separating the kids. The conditions that they are kept in are just awful. That is one of the reasons that we want to tell our story, because the people in the government are doing the same thing again, not only not again, but this is maybe the second or third time that they're repeating the same response. We want to tell the story so people know this happened and it's happening again today.”

The posts for this month often reference a woman from our neighborhood named Karen Burch, whose family lived in the J-Flats/Virgil Village area for many generations, including when the neighborhood became redlined. Burch turns 70 at the end of this month and her niece is currently fundraising for her birthday to support Karen as she continues working on a book about her family’s story.