Selling a Future: Racism & Rental Advertisements

An Interview with Computational Social Scientist Ian Kennedy

Most renters are familiar with the process of apartment hunting. You need a place to live, so you do some research. Maybe you ask friends or family who live in the area if they know of any openings, but this is usually not a fruitful strategy, because while they might be able to tell you a little bit or even a lot about the city or neighborhoods you’re looking at, they likely don’t know of the availability of local rentals unless they personally know someone moving out near them.

For many reasons, I am a firm believer in on-the-ground apartment searching, since that is how you best get a sense of a neighborhood before you relocate your life to that new place, but not everyone has the time or luxury to walk the streets of their future neighborhood, in which case they might turn to Craigslist. A quick search of the Craigslist apartment listings for the 21 blocks that comprise Virgil Village, the neighborhood in which I currently reside, lists (at my time of writing this on June 4, 2022) three apartments for rent. Last week when I checked, there were approximately seven no-longer-available listings in the same neighborhood, meaning these apartments go quickly.

The three current listings provide a good case study, though, so let’s look at them more closely. The most expensive of the listings is a supposed 700 sq ft 1 bedroom apartment going for $2,200/month. (I say “supposed” in terms of the square footage because my own apartment’s square footage is currently listed inaccurately on Zillow and on similar rental listing websites, so don’t believe what you read in these ads).

The description in the listing is as follows:

For those of you unfamiliar with this area, Virgil Village is a small area on the easternmost side of East Hollywood, which is located in central Los Angeles. East Hollywood, largely a working class Latinx community of renters, is adjacent to the much wealthier and whiter neighborhoods of Silver Lake (to the east) and Los Feliz (to the north). My collaborator, J.T. the L.A. Storyteller, has written fairly extensively about the historical policy decisions that led to the current racial and economic landscape in East Hollywood and its neighboring communities, but all of this is to say, what a listing agent calls a neighborhood says a lot about not only what they value, but about what they think you, the prospective tenant, should value.

For starters, the name people call a specific neighborhood can tell you a lot about how they relate to that neighborhood and whether they see that neighborhood as valuable or trendy. Many neighborhood names throughout the U.S. have evolved over time in response to developers, planners, businesses, and landlords trying to brand neighborhoods, making them more marketable to certain demographics. In the above listing, however, an apartment seemingly located near Virgil & Burns, is presented with conflicting neighborhood names. Just under the title of the post, we see “Virgil Village/Los Feliz Adj.” as the location, but the text of the post itself says “Great SILVERLAKE Location,” with Silver Lake in all caps.

Nowhere is East Hollywood named in this post, despite the fact that this apartment officially lives in East Hollywood. Even in that final sentence where the listing agent notes surrounding attractions and neighborhoods, East Hollywood isn’t named. Nor is East Hollywood’s economically-similarly-situated neighborhood to the south, Koreatown, named. What is named are wealthier, whiter neighborhoods—historically “greenlined” areas—like West Hollywood and Beachwood Canyon, all way farther from the apartment than East Hollywood or Koreatown.

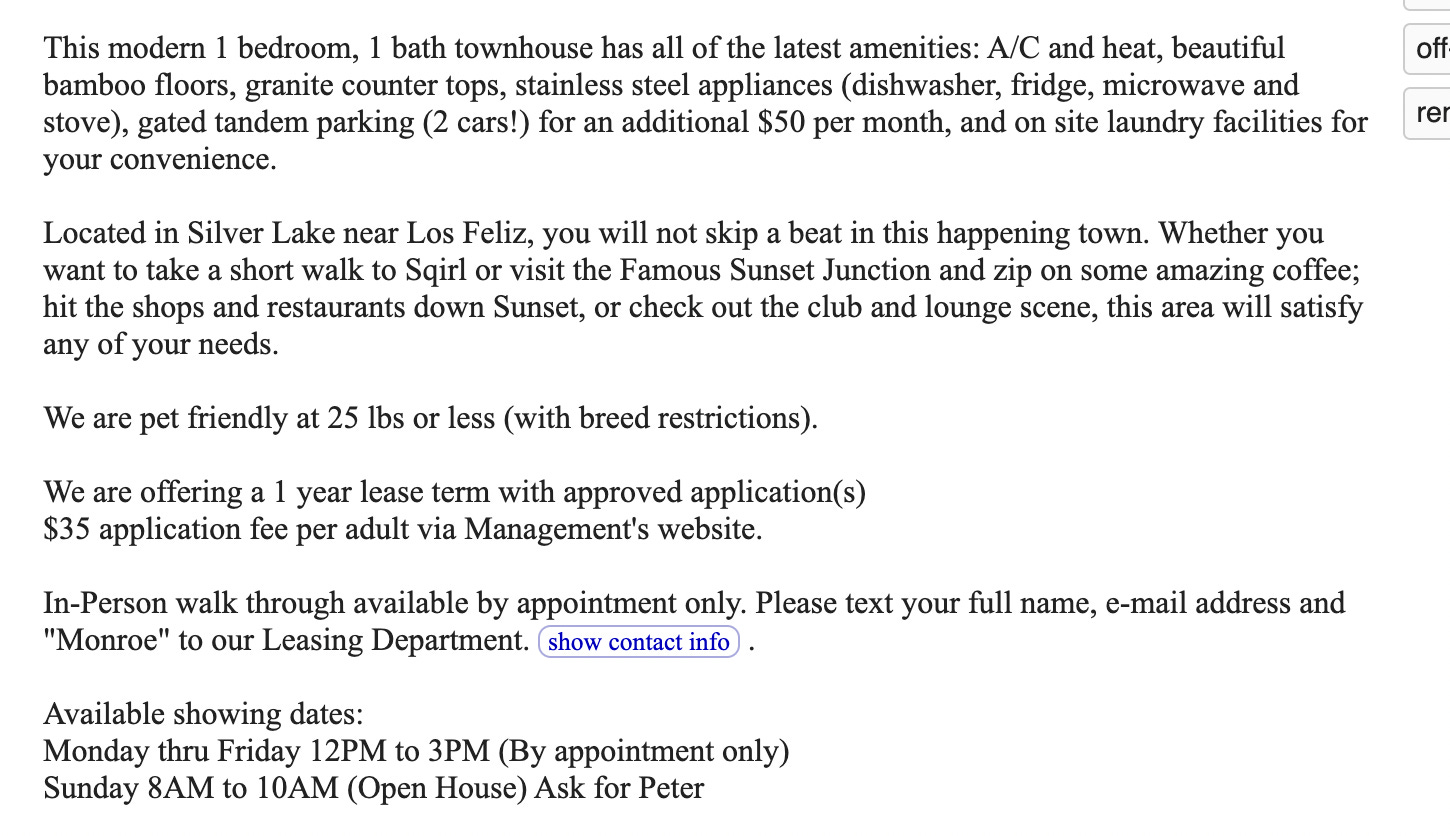

The second most expensive apartment available right now is a supposed 500 sq ft 1 bedroom going for $2,100/month, which is described as a “Silverlake Townhouse Gem.”

Again, note the location descriptors the listing agent or landlord wrote for this apartment:

This apartment, like the last one, lists only Los Feliz as a nearby neighborhood. The other thing both of these listings have in common is that the only restaurant, grocery, or hospitality businesses they list are Erewhon (a very expensive local grocery story) and Sqirl (a brunch spot), two relatively newer businesses in the area, both with very high price points that do not align with the economic demographics of the majority of East Hollywood. Samanta Helou Hernandez has previously noted that the ad listings for new condos in Virgil Village, condos that replaced local restaurant Cha Cha Cha in 2019, also boasted proximity to Sqirl and similar restaurants in the area.

The third Craigslist listing I found in my most recent search is the only listing that does not adhere to predictable real estate selling points. This one is also a 1 bedroom (no square footage listed), going for almost $300 less per month than the other two. The location for this listing still invokes Silver Lake, but this unit actually looks to be quite literally on the exact boundary between East Hollywood and Silver Lake.

The ad copy for this post is relatively minimal and talks about proximity to parks and public transportation, instead of bragging about proximity to expensive restaurants and trendy neighborhoods.

My interest in Craigslist rental ad descriptions arose not too long after I moved to this neighborhood and started to notice the stark contrast between patrons of local legacy businesses and newer, more expensive businesses. I wanted to see if developers, landlords, and listing agents would use these new businesses as a selling point, so I started looking. And over ten years of skimming these ads, it appears that that’s exactly what’s going on. So when I met a fellow academic who told me they had scrapped this kind of data from rental listings, I knew I had to interview them for our newsletter.

Ian Kennedy is a computational social scientist working at the intersection of race, digital platforms, and text analysis. Their work aims to contribute to understandings of how contemporary racism works, in both visible and less visible ways. This means looking for data in new places, like in Craigslist rental ad texts, or by developing new uses for large-scale administrative data.

Ian and I met earlier this year when the research collectives of which we are both a part—theirs the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, mine USC’s Media as SocioTechnical Systems—merged for a meeting and conversation. In that conversation, Ian told me about their work data-scraping rental ads, and eventually we both sat down in front of our computers for a long-distance zoom interview to discuss their work and their findings.

Ali: Tell me about your project! Where did it start?

Ian: I came to the University of Washington for a PhD, and I’ve worked with someone here who is a well-known person within the subject of neighborhood segregation. He had just come out with a book that asked, why is segregation still being reproduced 50 years after the Fair Housing Act? And he really focused on how purportedly nonracial decisions played into people making housing choices, especially in terms of rental housing choices, but also possibly in purchasing one. You can imagine people who act in racialized ways without thinking that race impacts their actions. I was interested in seeing, could we find some evidence of that process in the Craigslist ads or in other kinds of online rental ads? And it turned out that for other reasons, he had already started the process of scraping some of the ads with one of his other students.

So I joined that effort and started working on this idea that I eventually called the “racialized discourse.” I'm using racialized to mean, broadly, the result of a social process by which some person or place or thing is associated with a particular racial identity or group. So neighborhoods might be racialized because of their association with racialized bodies, and discourse (in my work) is racialized because of its association with racialized space. I'm still working on that with the dissertation where that first project was just focused on Seattle and now I have data from more places.

Ali: So what is the data scraping tool like? Can you kind of describe it for us?

Ian: Yeah, we are using a tool called Helena, which is a web scraping by demonstration program. It's a program that lets a user click through web pages and select what they'd like to scrape. Then Helena can automatically scrape that information across many similarly-formatted pages. It was developed by a computer scientist named Sarah Parsons, who worked with us, and she was at YouTube. Her main thing is, there's a lot of interesting data on the web. Social scientists and other non-computer scientists want to access it. How can I make that process easier? But anybody can scrape a page, so you could set up a scraper to scrape your local neighborhood rental ad listings using Helena if you wanted to. It's very easy to use.

The data I use comes from the UW's National Rent Project, which was started by Kyle Crowder, Chris Hess, and Sara Chasins in (I think) 2017. The goal at the time was to use scraped data to help Seattle-area housing authorities offer housing vouchers that were commensurate with the rising rents in the area. Because the housing authorities had been using slow-to-update HUD surveys, they were offering vouchers that weren't keeping pace with rapidly rising rents. With that goal in mind, the project tried to collect the asking rents from advertisements for rental homes on Craigslist. In practice, that meant going to the “apts / housing” section of the Seattle Craigslist page and then collecting as much information as possible about each listing there. We aimed to collect the rent, the listing text, the location, and details like the neighborhood name, the square footage, number of bedrooms and bathrooms—stuff like that. In 2019 we expanded the scraping to cover more than 100 metro areas, collecting the same information from as many ads as we could in each of those places.

I'm using the word racialization to name the outcome of the social processes that makes people (and their bodies), places (like neighborhoods), and things (like brands), show up as being associated with a particular racial group or identity. When I talk about racialized neighborhoods I mean places that are associated with particular racial or ethnic identities. We don't need to cite the census to know where the rich white neighborhoods are in our city or town (if we've lived there for a while). Those places have gained both raced and classed meaning that might change how interested we are to visit or live in those places. We know that those meanings are derived, at least in part, from racist segregatory policies like redlining and restrictive housing covenants, which not only maintained racial segregation, but also-—by making it very hard to get home loans in Black neighborhoods—enforced racial wealth disparities. So that means that in 2022, we have a racialized landscape of neighborhoods.

When I talk about racialized discourse, I'm talking about linguistic themes or phrases (like positive descriptions of the neighborhood), which are more common in neighborhoods racialized one way than in neighborhoods that are racialized a different way. A significantly larger proportion of advertisements in white and Asian neighborhoods include phrases like "great neighborhood", "prime area", and "location, location, location" compared to advertisements in Black or Latinx neighborhoods. It's very rare for ads to describe neighborhoods negatively, but it means that neighborhood descriptions in Black neighborhoods are more neutral (like just a description of nearby shops) or more likely to just be absent. I also use a computational technique called topic modeling, which produces similar results across a wide variety of positive words associated with the neighborhood.

Because my definition of racialized discourse is based on differences in prevalence, I can't use my data to make definitive claims about how those differences happen. That is, I can show that more ads in white neighborhoods have the phrase “great neighborhood,” but the data can't say why the people who wrote those ads decided to include that phrase, while people who wrote ads in Black and Latinx neighborhoods decided not to; however, I think I can make some reasonable speculations.

First, it's reasonable to expect that a fair amount of the difference is connected to the way that non-white neighborhoods have faced consistent and often explicitly racist disinvestment, while white neighborhoods have seen huge municipal resources for public amenities. However, I do this analysis both with and without controlling for socioeconomic status (income, poverty rate, prevalence of college education, among others) and housing stock (share of rental units, age of housing stock, among others). I find that Black neighborhoods are described less positively in both conditions, so it's not just structural differences in neighborhood status. I think a big part of it is that the racialized discourse in the advertisements reflects the anti-Black racist ideology that is common in the United States. This aligns with critical race theories about how race and place intersect, like in Richard Ford's 1994 paper "The Boundaries of Race," where he argues that racialized space will both perpetuate racial segregation and naturalize racial differences across space.

There are a couple of things about Craigslist which make it a particularly good place to do this kind of research. People posting on Craigslist have a lot of freedom in what they write. On other platforms, like Apartments.com, most of the listing is created by clicking checkboxes for amenities that are present (or not) on the unit or property. Apartments.com also assigns the listing to a neighborhood based on the unit’s location. In contrast, on Craigslist, landlords have no restrictions on what kinds of text they include in their listings. Ads can be longer or shorter, and include more or less information about the neighborhood, depending on how much the landlord thinks that information will help rent the unit. Craigslist also lets landlords fill out the ‘neighborhood’ field of the listing manually: they can say their unit is in any neighborhood they want, or they can use that field for other information.

I'd speculate that when people change those names, they change them either in anticipation of or in the same process of gentrification and racial turnover. If you did, for instance, segregation metrics using those spaces as named on Craigslist, you'd probably get higher segregation than you do when you do the metrics using census tracts, for instance. I'm interested in testing that. But just more generally, Craigslist lets you write whatever you want in there. So as you probably expect, just doing a search for a neighborhood name wouldn't work for collecting the data because people can just say [about Virgil Village], it's all Silver Lake now.

Ali: Right. Yeah. That's why, when my first instinct was to look for rentals in East Hollywood, I realized it was not going to turn up rentals that are, in fact, in East Hollywood because they're going to be listed as Silver Lake. And then there are places south of here, for instance South Central Los Angeles where USC is located. That neighborhood is historically called South Central. But after the ‘92 riots, there was a sort of push to rebrand. And I don't actually know enough of the history about where that push came from, but people call it South LA now, not people who are from there, not people that grew up in this city. But I think USC refers to it that way. And in fact, I've had editors at publications request to change my language, not call it South Central, but call it South LA. And I always have to add a little addendum saying it is called South LA now, but I'm referring to it as South Central, because that's a political choice to refer to that language, to refer to that neighborhood as South Central, which is kind of wild. But I'm sure it would be similar on Craigslist, people would list apartments as being located in South LA if it's a new developer, or maybe they have a different, more specific name for parts of that neighborhood. It makes the data hard to parse.

Ian: Jackie Horn has a really good paper about that exact process happening in Philadelphia. She interviews people from South Philly in general I think and documents how new white residents called the area their own special thing. I forget what they call it, but they carve out a space that's that. And then they have a separate definition for South Philadelphia as being south of their place.

Ali: Yeah, that's wild, but also predictable. So what kinds of expectations or hopes do you have around what you can learn from this research, or around what you can share with an audience from this research?

Ian: I think there are some interesting practical things that we can do with it. I'm working with the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, which I think everyone just calls CAFHA, and they have been working for a while looking for ads that exclude heavy holders. And actually, I've done this with a legal aid group here in Seattle, too, so we can use the ads to say, oh, here are the places, here are the ads, here are the landlords who are saying “no section eight.” And in places like Chicago and Seattle, that's illegal. So we can then ask those landlords to stop. We've been doing that in Seattle. They also do that in Chicago. But then we're also starting to think, well, who are the landlords who are just continually saying “no section 8 housing” in their rental ads and where are those landlords located across a city or across the country?

What is less practical but maybe motivating for me and maybe eventually could be useful is, I borrow this idea from Kathy Cohen, where she has this great metaphor of there being systems of oppression and there being what she calls a “fabric” that's supporting them, that allows those systems to persist. And I really like the metaphor of fabric because it shows you two layers that systems of oppression can have.

On the one hand, these systems really show up as single, unitary forces that do harm. But I think then you can zoom in on them and see that, oh no, they're made up of all these threads of everyday social activities that then have some kind of friction together, that keeps them woven together. That fabric is really complicated, but one way to think about that intersection is there being a structural set of threads and an ideological set of threads that are holding onto each other. And I think that it can be really powerful to disrupt that intersection. This is one place where a thread can overlap, where there's this structure of racialized housing outcomes, which causes all sorts of problems. It's a really long thread. And then one place where that thread intersects is with the way that racialized ideology happens in housing ads. Can I zoom in on just that one place and see or understand more about the friction holding these two together, and then could we do that in other intersections? Also, can we learn ways to disrupt the threads by understanding more about those places? That’s less immediately practical, and maybe more like long term hopes.

Ali: That's so fascinating, that fabric metaphor, because it visualizes something so complex and hard to visualize. We talk about these kinds of issues, systemic issues in these broader terminologies, but we don’t always see the connections. With this newsletter for instance, our neighborhood, East Hollywood, is one of many neighborhoods in LA, and LA is one of many cities in California and in the United States in general. And so we’re asking, what can we learn about what's happening in our neighborhood? How can we document what's happening in our neighborhood not only to preserve what once was, which is this predominantly immigrant, low-income Latinx community history, but also, how can we then draw those connections with similar intersections of systemic issues in cities like Seattle or in cities like Chicago or Philadelphia or elsewhere across the country? So that the work becomes more about saying, okay look at these two little threads intersecting, but that one thread, that housing injustice thread, it doesn't just pass through Los Angeles, it passes through every single neighborhood and city and town in the country.

Then if you can tear away at that housing injustice thread, even if only one of those threads is the racialized language in the advertisements, and then another thread is historic redlining and how that has impacted what is available for investment, I think that's a really interesting way to look at tackling systemic racism.

Have you encountered anything particularly surprising from doing this work?

Ian: This is not a direct answer to that question because I don't think it's necessarily surprising, but I want to use it as an opportunity to talk a little bit about seeing people who are less subject to anti-Black racism or are explicitly resisting it. Because I think it also connects to what you were just saying about, how do we unravel the fabric? One of the big findings in the first chapter of my dissertation is, kind of unsurprisingly, Black neighborhoods are described less positively than white and Asian neighborhoods. When you compare high income white and Asian neighborhoods with high income Latinx neighborhoods, they look pretty similar. But then when you compare low-income white and Asian neighborhoods with low-income Latinx neighborhoods, they look very different.

Ali: In what way?

Ian: White neighborhoods that are poor are still described much more positively than poor Latinx neighborhoods. But rich white neighborhoods and rich neighborhoods of color (specifically Asian and Latinx neighborhoods) are actually described somewhat similarly compared to Black neighborhoods, which are described less positively across all income levels. That by itself is interesting. It's not new information, but it just connects to the fact that we know that racialization, ethnic racialization, happens very differently for Black Americans than for almost everybody else..

Ali: Are you looking specifically at that as an example in Seattle or that's in other cities as well?

Ian: My dissertation is a sample of 16 metropolitan areas, so that's looking across those 16 metropolitan areas.

Ali: What are the areas?

Ian: Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Riverside, Colorado Springs, Dallas, Atlanta, New Orleans, New York, Boston, Providence, Chicago, Honolulu, Charlotte, Philadelphia, and Worcester Mass.

Ali: What was the selection process for those areas? I'm from Colorado, I grew up outside of Denver, and Colorado Springs feels like a really interesting choice given all the cities and towns in Colorado.

Ian: I wanted difference or variation across a couple levels. I wanted a regional variation. I wanted variation in terms of the city's history of segregation. I think that's one of the things that Colorado Springs did, because it was probably a lower segregated city. I wanted some variation with the size of Worcester, Massachusetts. I wanted some smaller metropolitan areas. I think those are the main things, but I wanted to limit it. We have data on all of the 100 largest metropolitan areas, with some fudging, like Honolulu technically isn't one of them, but I more or less insisted that we include it because it's the only one that has large AAPI and large native populations. But I think that I really wanted to have on-the-ground relationships in as many of the cities as possible. So a little of the selection also happened based on thinking about where I already had some connections. A lot of my family is from Worcester. I grew up in New York. I've spent a lot of time in some of the other cities, or I had existing connections to organizations in them, that kind of thing.

As we get more years of the Craigslist data, we hopefully should be able to track the emergence of new neighborhood names. We kind of expect that new neighborhood names usually come with a rent increase, but can also usually be associated with other measures of gentrification that would then be associated with changes in racial turnover, stuff like that.

Ali: So is the plan to do a longer term data collection over a period of years and then track different aspects of what you interpret from that data?

Ian: Yeah, that's the hope. It's interesting. There are some differences in Craigslist and apartments.com ads. Apartments.com writes their own neighborhood descriptions, but not for every neighborhood. Some neighborhoods, they just get a city description instead.

Ali: And you're looking at rentals rather than like homes for sale?

Ian: Yeah. Almost exclusively rentals.

Ali: Because that's one aspect of gentrification, right? The rental market. And then another aspect is the home buying market where in places like Highland Park (in Los Angeles), for instance, there is a lot of home buying happening there from new white residents in a predominantly Latinx neighborhood. I think there's also an increase in white renters. But a lot of times when I hear white folks talking about buying a house in LA, it's in the Highland Park area. So I wonder if there's similar stuff going on in terms of how people list homes. I haven't really looked at home listings and what kinds of language they use. I feel like it's more focused on the house itself rather than the neighborhood when I have looked at those things. But I'm curious if they use similar kinds of language around advertising the home for sale.

Ian: Yeah, I also haven't looked at them. One of the reasons that this project was scraping rental ads specifically was because there isn't really good data on what asking rent is in a given city. And so we were kind of thinking maybe we could fill some of that gap. And we do a lot of research, the other parts of the team do a lot of research using that aspect of the data, whereas home purchase prices are well documented. And I don't think that it would be different. But I agree with you that it would be hard to do it within the same analysis, right? Because the goals of someone selling a house are so different from the goals of someone renting a house. I think if anything would be similar, the neighborhood descriptions would be similar. Because in both cases, you're selling a future to someone.

In terms of some of the racialized discourse, that's because it's pretty consistent across cities, like it doesn't matter where you are. White and Asian neighborhoods are described more positively than Black and Latino neighborhoods everywhere.

Ali: Right, which is an interesting thing to be able to prove with data. I mean, it's a thing that we can talk about from more of a cultural studies perspective, it's a thing that we know from lived experience, felt experience, but social science gives us a way to put data to what we feel or observe, which can be important in terms of getting people to believe it. But then the question always becomes, is it a matter of people not believing it, or is it a matter of all of this happening intentionally and we know that it's happening intentionally, so then who are we trying to convince that it's happening intentionally? Because the people who are doing it already know they're doing it intentionally. Who else are we trying to convince?

Ian: That's a really deep question for me. This is when you think about the intentions of people who are posting ads. There are undoubtedly lots of good examples of intentionally racist action in the history and present of the United States that are clearly central to maintaining segregation. But it's reasonable to expect that a lot of the people who are posting the ads that I'm talking about are doing the racist thing because it just feels like the right thing to them. One way of thinking of that question for me is, are these people using racist ideology or is racist ideology using them? And I think there's a reasonable balance there where there are definitely some people who are using racist ideology and probably some people who are being used by racist ideology. And I think there are enough people being used by racist ideology for it to be worth it to try and fight against that racist ideology explicitly. How do you do that? What would that look like? I feel like I'm less well suited to answer that part of the question, but it's worth saying that the effort to fight that racist ideology could pay dividends if we were effective.

Ali: Yeah, I think for me, that's the work of organizers and educators, to bring people into thinking about that stuff, bring people into questioning their relationship with those racist ideologies and then educating people. And when people are educated, people who are newly aware of that racism can take anti-racist action. If you're talking about racist action, then the counter to that would be then taking anti-racist action. What does that look like?

Ian: They are definitely people I found by doing a close reading of one development company in West Philadelphia that's explicit about supporting Black Philadelphians, and not surprisingly, their ads about West Philadelphia are much more positive than other ads about other Black neighborhoods. I found them by doing quantitative analysis, by looking for Black neighborhoods that were described more positively than the model expected them to be. And one of them was where this property holding company had a few properties. I think that it really matters if the people who own the properties and are writing the ads have a real connection to the neighborhood. And that probably means they live there and have lived there for a long time. So I think it’s reasonable to say, hey, the people who live in a place have rights to that place and those rights should really be ownership rights. Whatever we can do to support people who have lived there for a long time to be able to be owners or landlords, if we have to have owning, they should be the ones owning. There's a push right now in Seattle to develop a social housing arm that would be mixed income by design and would be then accountable to citizens. I think that there's a real potential there.

***

This interview has been edited for clarity. For more information about Ian and their work, visit their website at https://www.ian-kennedy.com/.