The Eviction Machine in Los Angeles

How Giovanni Rodriguez lost 29 years in less than four weeks of Eviction Court

I first received a text message about Giovanni’s eviction on March 2nd, 2024, just three days before the primary election which took place that week. I didn’t get the text directly from him, but from a friend in the neighborhood who had learned about his story a day before. While a few names came to mind in terms of a referral I could provide, I was laser-focused on tracking results from the election that week and so I didn’t reply right away. By mid-week however, I happened to spot a flyer for a local Tenants Union meeting taking place at Lemon Grove Park on March 9th, so on Friday afternoon, I sent it to my friend and asked him to forward it to Giovanni. I wasn’t exactly sure if Giovanni lived locally, but since my friend first met him at L.A. City College, I figured there was a good chance he was familiar with East Hollywood to an extent.

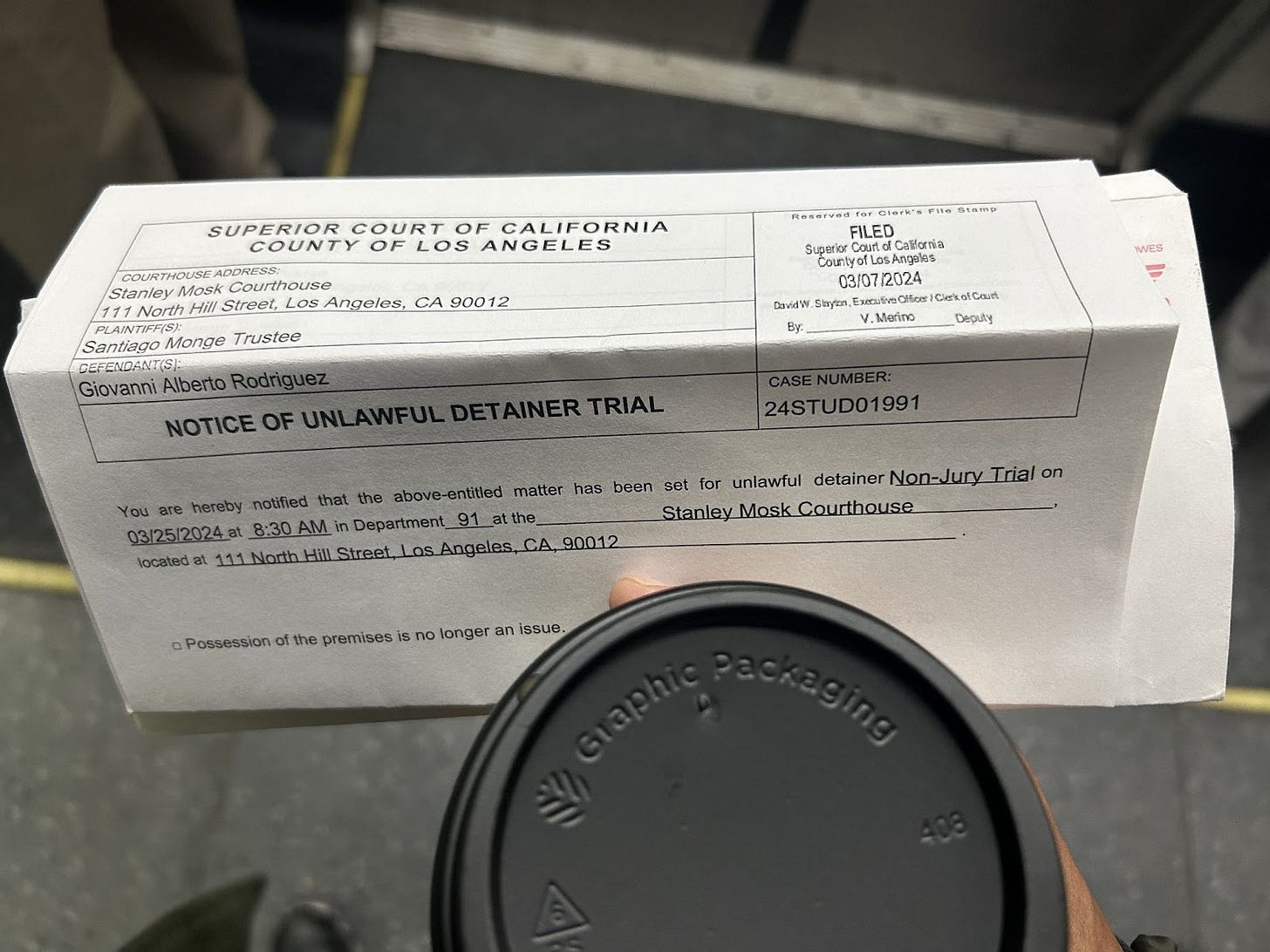

I also hoped Giovanni could make it to the meeting despite a rather late notice, but I wouldn’t know for certain until two weeks later when we actually spoke over the phone on March 22nd. Giovanni informed me then that since he doesn’t own a car, he took an L.A. Metro bus to the area and then walked to Lemon Grove Park, reaching it slightly after 2 PM, when the meeting was supposed to start. But when he didn’t see any Tenants Union representatives tabling, he figured that the meeting was over or that it just hadn’t taken place after all. He also noted to me that his court hearing was set for March 25th, just two and a half days out. When I asked if he’d been in touch with his landlord at all after the notice, he told me that he hadn’t.

That night, I reached out more directly to a few attorneys who I thought could be of support, though not to any outright Tenants Rights attorneys. But in each case, like Giovanni for the Tenants Union meeting, I just wasn’t exactly on time given the proximity of the court hearing on Monday morning. The only thing we could hope for, I would come to learn from one of the attorneys I’d briefly gotten in touch with, was a plain and simple postponement of the hearing so Giovanni could have more time to find proper legal counsel and representation.

On Saturday over the phone I asked Giovanni if anyone would be going to court with him on Monday. He replied that he planned on going alone, so I proposed to accompany him to document the process, which he agreed to. On the morning of Monday, March 25th, I met with him at Metro’s Vermont/Santa Monica station, after which we boarded Metro’s B Line going south.

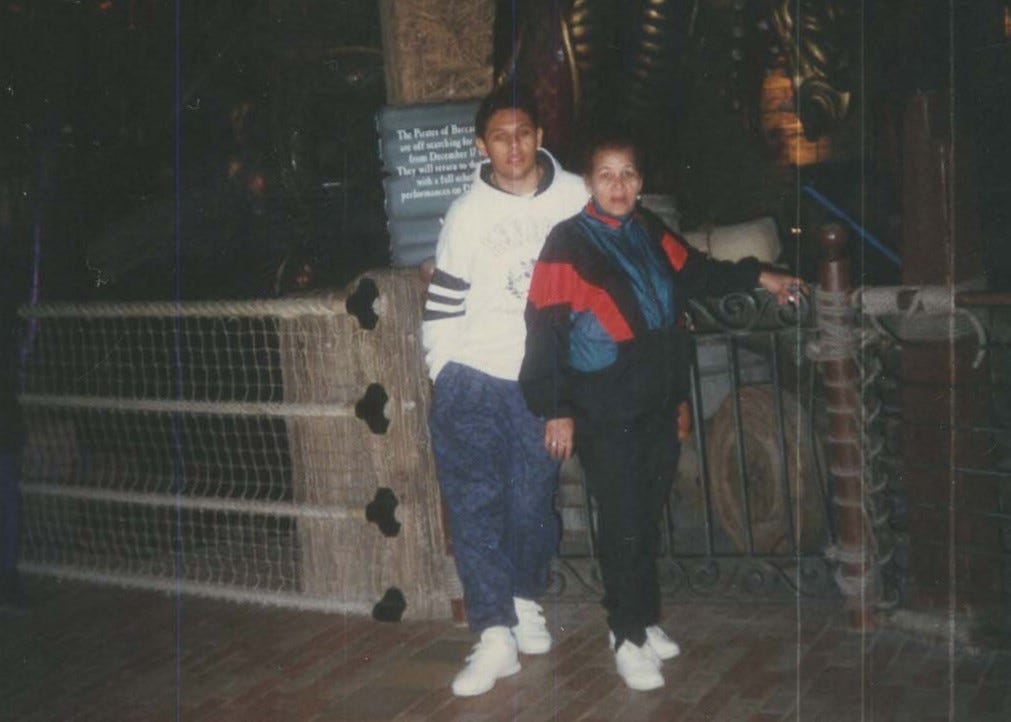

Giovanni first arrived to Los Angeles with his parents, Bolivar José Antonio Rodriguez and Rosa Nereida Yubank in 1994. He was only 19 years old then, while his mom was 58 and his dad was 68, but unlike many Latin-American families coming to the city at that time, he and his parents did not migrate by land, but entered the U.S. as residents thanks to a petition filed by Giovanni’s uncle ten years prior; the fact that Giovanni’s father was an engineer back home in Costa Rica helped significantly in the petition’s success. One year later, he picked up his first job at a McDonald’s in East Los Angeles.

Giovanni worked in the fast food industry for four years, followed by work in hotel maintenance until 2001. All the while, his parents were not far, renting out an apartment just a few doors down from him at 1318 North Virgil Place in East Hollywood. His dad earned his living working as a small contractor in construction and building maintenance, while his mom stayed at home to take care of the family. But since his parents got to the U.S. relatively closer to their retirement years, time would shift life around the home before too long.

In 2007, Giovanni saw the birth of his first and only son, Victor. But that year he would also see his mom’s health decline significantly due to her battle with Type 2 Diabetes, which she had been diagnosed with even before she’d arrived to the U.S. from Costa Rica. At that point, he was working as part of a security detail team, but the following year he left that job to become an In Home Supportive Services (IHSS) provider, which actually allowed him to stay home and earn a small living while caring for his ailing mom. After seven years of this arrangement, Doña Rodriguez succumbed to a bout of pneumonia in 2014, passing away at 78 years old; she was survived by Giovanni, his father, and an older sister seventeen years older than Giovanni who he didn’t grow up with.

By 2014, the world was entering a new phase politically, technologically, and socially, but for Giovanni, it was also changing personally. Only a year before his mother’s passing, he and Victor’s mom separated, with Victor going off to live with his mom. Giovanni continued working as an IHSS provider, caring for his aging father, but by 2018 he also picked up a job with Universal Studios on a seasonal basis. However, in 2019 his dad passed away at 88 years old, which also meant Giovanni would no longer be able to work from home as an IHSS provider. According to Giovanni’s uncle on his dad’s side, Don Rodriguez should have left some money for Giovanni upon his death. But Giovanni noted that this money would be split between at least three other siblings in Costa Rica and he and his older sister in the U.S. And since it was very expensive to send his father’s body back to Costa Rica, there was very little he was actually left with.

A year after his father’s passing, the pandemic began to take hold, bringing with it another slew of changes. Giovanni’s seasonal work at Universal Studios was placed on an indefinite hold. Around this time, he began looking for other work while also making use of the eviction moratorium passed by the L.A. City Council and supplemented by the L.A. County Board at the beginning of stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders. But near the end of 2020 was also when L.A. Metro began to roll out its NextGen bus programming, which canceled a substantial number of bus routes and schedules; this grossly impacted Giovanni’s ability to get to work in places such as Glendale, where he was scheduled for shifts at a fast food restaurant as early as 5:30 AM. Moreover, around this time during one of his shifts Giovanni experienced some major back spasms when applying too much pressure while lifting materials. To this day, the issue has substantially limited his ability for typical manual labor employment.

Giovanni continued paying for rent at his apartment for about a year, but in late 2021 he applied for rental assistance with L.A. County. The program helped him to cover his rent expenses for 18 months but expired at the beginning of 2023. Since then until March of this year, Giovanni has been unable to pay rent. This past February in L.A. is also when all back-rent owed by tenants was due in full based on a decision by the L.A. City Council, as well as when rent-increases from 4 - 6 % on RSO units in the city of L.A. were slated to take effect, also due to a decision by L.A. City Council.

When Giovanni and I reached Civic Center station, we stepped out and made our way up to the Stanley Mosk courthouse in downtown Los Angeles, where his case was scheduled for a hearing. By 8:30 AM, we had gotten past the security check-point at the entrance and reached the 6th floor of the courthouse. We found his case number on a sheet posted next to the courtroom’s doorway and then waited with about a dozen other people gathered in the hallway outside of the courtroom. The room was the second to last down the hallway, and when I took a moment to glance down the path we’d walked to reach it, I saw a long hall bustling with scores of people. I wondered who was there for family court versus a parking ticket or a more serious case. It then dawned on me how this was a daily occurrence through Los Angeles five days of the week and for hundreds of thousands of people, if not more.

A few minutes after 8:30 AM–before the doors to the courtroom officially opened–a legal representative for the plaintiff, or the landlord, approached Giovanni and I; after confirming that Giovanni was the right defendant, he simply asked about how much time he needed to move out. I translated this for Giovanni, who is an English language learner, and the translation made him visibly nervous, as though its gravity jolted his nerves too quickly. Upon registering this, I replied to the representative for the landlord that Giovanni was just seeking more time to consult with legal counsel. The representative then shook his head and walked away while noting matter-of-factly that “the trial [was] today.” It was true that a “non-jury trial” was set for that Monday morning, which is when a judge hears and decides the case in lieu of a jury or randomly selected jurors, although even this was only the case after Giovanni had filed an Answer (form UD-105) responding to the Eviction Notice within 5 days of receiving it.

After Giovanni’s Answer form had been received, the landlord requested a non-jury trial, setting the date for March 25th. Giovanni could have then sought a trial by jury contrary to the landlord’s choice for a hearing, but he would have needed to fill out a separate Request (form UD-150), which also would have cost $150. At the time, Giovanni didn’t know this, but in actuality he wouldn’t have had the $150 to pay for a trial by a jury of peers anyway, though it would have been standard for a defense attorney to take care of the Request and a fee waiver on his behalf. In turn, even before entering the courtroom, Giovanni was already playing on the landlord’s terms.

A moment later, a sheriff opened the door to the courtroom and asked the dozen or so of us waiting to find our way inside. Each of us proceeded to fill up the rows of seats before the judge’s floor; while our cohort that morning was of varied backgrounds and age ranges, at least one other defendant in the courtroom that morning was a Latino, and most likely in his early twenties. As it happens, it was a bit of a rarity for the courtroom to see only a few Latinos that morning, including Giovanni, which I made a mental note of when I overheard a clerk for the court note that “we only need a translator for one this morning, miraculously.” The young Latino man’s case would be called before Giovanni’s, and we would see him agree to pay $9,000 in back-rent within the month or face eviction.

The judge overseeing cases that morning was Andrew Esbenshade, who was only appointed to the L.A. Superior Court by Governor Newsom in 2023. As we waited to be called, the goal for Giovanni was just to be granted more time by judge Esbenshade to consult with legal counsel or obtain proper legal representation. At least this is as much as I understood going to the courthouse with him that morning. We had discussed this a day prior to the meeting time and during our train commute, and even when we were seated and waiting to hear his case number called, Giovanni and I quietly reiterated this to one another as though to keep both of us focused on what to respectfully make a plea for. A few more cases were settled before Giovanni’s was called, which was referred to at that point as “number 26.”

At approximately 10:30 AM, when Giovanni’s number was called, he stepped past the open doors and went up to what is known as the courtroom bar table, where ideally he would have been met by a defense attorney. Instead, he was only met by an interpreter provided by the court, while the plaintiff and his attorney stood opposite of him to his left side. Giovanni’s eviction case was a civil and not a criminal matter, after all, only the latter of which have the legal right to an attorney. In California the only exception to this legal framework is in the city of San Francisco, where in 2018 voters passed a right to counsel for all tenants facing eviction within the city. According to Cal Matters, “Nationwide, fewer than 5% of tenants in eviction cases are represented by an attorney, compared to more than 80% of landlords.”

Standing before the bar table, Giovanni heard judge Esbenshade read out a summary of procedures relevant to the eviction process, just as he had with a handful of cases before his, and as he would do with a handful of other cases after Giovanni’s before it was time for lunch. A moment later, when judge Esbenshade asked Giovanni if he would be willing to settle the matter with the landlord outside of the non-jury trial, instead of pleading for more time as we had gone over, Giovanni confirmed that yes, he was willing to “settle.” This led to judge Esbenshade quickly pausing the procedure and allowing a private discussion between Giovanni, the plaintiff or landlord, and the plaintiff’s attorney outside of the courtroom. Their conversation wouldn’t last more than 15 minutes, and in the end, Giovanni agreed to vacate his home of the last 29 years at North Virgil Place within 30 days.

In scouring online for resources to include in this story, I happened to come across a quote that spoke directly to Giovanni’s experience at the L.A. Superior Court that morning. In a case known as Williams v. Schaffer (1966), the defendants attempted to fight a warrant for an eviction on the grounds that they were simply unable to pay rent as well as the legal fees associated with an official counter-affidavit. The court ignored these pleas, sided with the landlord, and had the local sheriff evict the tenants. Appeals by the tenants in higher courts were subsequently denied, and the following year, when The Supreme Court decided not to hear the case, Justice William O. Douglas wrote the following about the court system’s disproportionate efficiency for landlords and not renters:

“Summary eviction proceeds are the order of the day. Default judgment in eviction proceedings are obtained in machinegun rapidity, since the indigent cannot afford counsel to defend. Housing laws often have a built-in bias against the poor. Slumlords have a tight hold on the Nation.”

Since Giovanni’s agreement to vacate his home before the court, his older sister has helped him get in touch with the Salvation Army in Hollywood in hopes of obtaining a bed for him there soon. But at the time of this writing, as of April 10th, Giovanni is still on the wait-list. In an email-exchange with representatives for Hugo Soto-Martinez, the official representative for Council District 13, a staffer noted that there were also no Winter Shelter beds available at the moment through LAHSA (L.A. Homeless Services Authority). In subsequent emails with the Council Member’s office, staff also noted that there may be a chance to appeal the judgment depending on the circumstances, but this remains to be seen. Nearly a year ago, Council Member Soto-Martinez’s office had similar news for constituents about the number of beds available relative to the amount of unhoused people on the streets of Council District 13: “The City has fewer than 400 interim housing/shelter beds for the over 3,000 people living on the streets in our district…nowhere near enough.”

In December L.A. City Controller Mejia’s office also released this map showing that Council District 13 (Hollywood) was second only to Council District 14 (Downtown L.A.) in terms of the number of evictions filed in 2023, which is the year when a brief halt in eviction proceedings due to the pandemic officially came to an end; according to Mejia’s office, nearly 9,700 evictions were filed in Council District 13 between February and December 2023. In the category of neighborhoods alone, Hollywood and the 90028 area topped the list for evictions with nearly 5,200 cases filed. Mejia’s analysis of the data also states that 96% of all eviction cases filed in the city of L.A. were due to non-payment of rent.

Giovanni’s story is thus just one of thousands in this central portion of L.A., which Council Member Soto-Martinez once called “the most beautiful district in the city,” and one of tens of thousands of evictions in the city since just February of last year and in the pandemic era’s postmortem. For now, as Giovanni’s last day in his one bedroom apartment soon approaches, his belongings are already packed up into three suitcases. While he doesn’t know where he might go next, he’s remained in good spirits each time we’ve spoken, noting that what keeps him going at this point is his love for Victor, who is now seventeen and just on the verge of applying to college.

A week after the hearing, when I walked through his place to take a few photos for this story, I asked Giovanni what he’d been eating, to which he replied not much other than beans, although he was running out of even those.

“My grand-mother used to tell me that as long as you have a roof over your head and a plate of beans, there’s nothing to complain about,” he told me.

In a recent conversation with L.A. City Council Member Eunisses Hernandez, the Council Member noted that neither she nor her progressive colleagues at L.A. City Council could by themselves nor as a small cohort make citywide changes—such as ensuring renters like Giovanni the right to a defense attorney when facing eviction— without more support from their colleagues on the Council. As the city verges on electing not one but two more progressives to L.A. City Council in this November’s elections, then, including a former Tenants Rights attorney in Ysabel Jurado, the support Council Member Hernandez is talking about may be closer than ever. But for now, for renters like Giovanni, there is simply little to no recourse through the city’s channels no matter who’s in office, making the city and its public leadership appear farther than ever from those who need it most.

J.T.

Thank you for bearing witness to what's happening in the courts to so many confused and unaided Angelenos. We've added Giovanni’s bungalow court home to our map of these historic RSO multi-family buildings (https://esotouric.com/bungalowcourt), and very much hope he's able to find a safe place to land.

City Council Speach by Anne Simon

It seems after looking through the archives of past city council meetings that the issue of police misconduct, brutality,corruption and unfortunately costly lawsuits that have drained this city of much needed funds for more worthwhile causes, than compensating citizens who’ve been mistreated, denied justice, betrayed in fact by the public servants we’re supposed to look up to and respect, expecting their protection when the real bad guy comes along.

I’ve personally witness vast amounts is misconduct, brutality, sex discrimination, obstruction of justice, nepotism, favoritism , sexism, misogyne, malicous prosecution, conspiracies to illegally evict innocent law abiding citizens only to then move in for the kill, the looting of said person’s entire estate, to seize all valueables ll lueables for the purpose of personal gain. We’re talking about Racueteering , conspiracies between the Cops, specifically Sg.t Braun of Central and the unscrupulous slumlord don toy, to rape and plunder expensive antiues, mink and sable fur coats, hierloom jewlery, collectors vintage clthing, movie memorabelia, fine art, ect.

Then , with the cops protecting him, Don toy proceeds to just two away cars, Ford Explorers, Range Rovers, puts an illegal lien sale on them, selling the stolen vehicles for profit.

Later, back at the ranch, maybe over some egg rolls the men lean in to split up the spoils of the war on elder, disabled widows. All right under your noses, and the cops won't; ever allow me to file a stolen vehicle report. Now I’ve been falsely arrested 10 times, while the cops protect the labor trafficker, I guess the cops are getting a cut of my pay too.

Basic Constitutional Rights-Issues are being trampled on

Then we have the constitutional issues, No man shall be deprived of property or liberty without due process?

And the punishment shall fit the crime

Equal protection under the law

And we have a new and generous ordinance that the homeless shall

not have their cars towed. Just after the city, my government allowed a criminal to move in and put me out of my home, they then took away my transportation, that WAS my new home. Without any action or adequate response from councilwoman Hernandez office, vague referral to nowhere.

Why no handicapped parking at the courthouse, that’s a federal violation. Then Don Toy refuses to let me into my home to retrieve my remaining belongings, and no civil standby will ask or demand that Don toy take the boards and bolts off to let me in.

NO judge, no sheriff, no notice, taken off guard.

3 Judges, a Clerk and a Bailiff: falsifying court docs

Obstruction of . Justice, Perjury Civil rights violations

Conspiracy to cover up crimes of criminals

Betrayal of the American Public: betrayal of justice

Then I write a long letter to Hernandez office begging for help , and a lot of other agencies I thought might have a say in this. And all i got was a “so sorry that happened to you.” And some generic vague advice about adjudication of these issues, without any action at all , no even a phone call. I literally demanded that the city give me back my car because of the fact that I’ve been in a labor trafficking trap for 7 years, no thanks to Hernandez who was advised of this 5 years ago, and her people did everything in their power to get me out of their office. No concern for my complaint, only an attempt to avoid embarrassment NO help1