The Fight for L.A.'s Last Japanese Boarding House

“I know it's labeled a boarding house, but it was more like a community center. It embraced everyone.”

It’s a muggy morning in May and 70-year-old Edith Fukutomi sits on the porch of a nearly 100-year-old boarding house on Virgil Avenue. Its wooden, square facade is now painted black and white, a stark change from its original off-white with light pink trim. An elderly Japanese man peeks his head out of the front door, and Edith introduces herself in Japanese and explains that she grew up here. They exchange pleasantries before the man heads back inside, leaving the door ajar so she can take a look inside the place that shaped her upbringing and provided a livelihood for her family for two generations.

It’s an emotional moment for Edith, who hasn’t been inside the 23-room boarding house in nearly two decades. “Oh my goodness,” she repeats in awe as she looks around and points out where things used to be, the changes that have occurred, and the fixtures that remain intact. “This is where my mom used to ring the bell to call the men for breakfast, lunch, and dinner,” Edith explains, standing in the dimly lit hallway of the house.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, boarding houses like this one existed as a refuge for waves of Japanese immigrants in Los Angeles, housing mostly men who worked as gardeners, laborers, and farmers, and needed an affordable place to live where they could speak their language. After WWII, this type of housing helped the community get back on its feet as people returned from internment camps. The families who owned these properties often lived on-site where women took on a significant role in cooking meals and maintaining the boarding houses. Today, only five of these kinds of properties still stand in Los Angeles, but the one on 564 Virgil Avenue is the only one left that continues to operate as a boarding house to this day, according to Lindsay Mulcahy, a community member and neighborhood outreach coordinator for the LA Conservancy, who spearheaded a recent historic cultural monument nomination for both houses.

Edith’s mother, Shizuka Ozawa and her aunt Doris, took over running the day to day operations of the boarding houses from her mother-in-law who built the multi-unit dwelling in 1924 to house single Japanese laborers. Every day, Ozawa cooked meals for the men, cleaned, and helped them settle into a new country as comfortably as possible. Edith remembers as a little girl having to help her mother prepare both Japanese and American lunches for the men before going out to play.

By the 1960s, the Ozawas owned multiple properties in the Japanese enclave known as Madison/J-Flats, just south of Virgil Village in East Hollywood. The two boarding houses located at 564 and 560 N Virgil Avenue sat on the same property as their two family homes on Commonwealth Avenue, just one street east of Virgil Avenue.

Back then, there were no fences separating these properties, which created a sense of community for the family, the boarders, and the children from the neighborhood who came to play in the backyards amongst fruit trees, grape vines, and a koi pond.

“I don’t remember it ever being empty,” Edith explains. “It was a refuge for many people.”

Today, the neighborhood has changed greatly but the two boarding houses remain intact, and are now protected due to a historic-cultural monument designation that passed in June.

Perhaps most significant is that the 564 building continues to serve as a boarding house for single, elderly Japanese men who’ve lived there for decades. While the historic-cultural designation protects the structures and ensures their survival, it does not protect the seven long-term tenants who, according to a coalition fighting to protect their right to stay, have faced harmful living conditions and a push to move out from a new owner who bought the properties in February 2021 from the Matayoshi’s, the final Japanese family to own the boarding houses.

Their presence in these boarding houses not only serves as one of few examples of affordable housing in the quickly gentrifying neighborhood, but also continues a nearly 100-year legacy of the L.A. Japanese community fighting to stay despite a history of discriminatory policies and displacement.

NEW BEGINNINGS:

The story of East Hollywood’s two Japanese boarding houses begins with Tsuya and Sukesaka Ozawa, two Japanese immigrants who were instrumental in building and supporting a community for others like them in the neighborhood known as Madison/J-Flats, according to Mulcahy’s historical monument nomination.

Sukesaka was the second son of an agricultural family from rural Japan and therefore would not be inheriting the family’s wealth. In 1902, along with a wave of Japanese migrants who came as a response to a need for railroad and agricultural workers, he decided to try his luck in California, where he settled in the Central Valley as a farmer.

Tsuya was an educated woman from a prominent family of the same prefecture who had lost her husband in the Russo-Japanese war and refused a life of servitude to her late husband’s family. She set off for California, sailing on a vessel to marry Sukesaka, who had sent her a photo of him in a sharp tuxedo standing in a farm. Upon arrival, she realized he didn’t own the farm and had very little money. Tsuya became one of 20,000 so-called “picture brides” who arrived from Japan around that time.

The new couple made their way down to Glendale a year later in 1910, where Sukesaka worked on a strawberry field and eventually settled in what would become J-Flats. There, they ran a produce stand on Heliotrope and Melrose Avenue. Tsuya, who was smart and industrious with a college degree, saved up money and began purchasing property.

The first purchase was their home in 1914, a bungalow built by Charles K. Akerly in 1912, at 564 N Virgil Avenue. By 1924, they had moved their humble house to the back of the property and built the wooden boarding house adjoining the bungalow. Next door, another Japanese family had also converted a bungalow built by the same architect into a boarding house and employment agency for single Japanese men. At the time, recent Japanese immigrants mainly worked at produce stands and as gardeners for wealthy, white families in Hollywood and Los Feliz.

“My grandmother hardly knew how to speak English, but she was incredibly smart,” explains Joseph Ozawa, Tsuya’s grandson and Edith’s cousin. “She made all this money on the fruit stand and used that money to buy the boarding house.”

The Ozawas made sure the boarding houses were markedly Japanese. They built koi ponds in the front and back of the property at 564 and even created a Japanese-style bath house. The women cooked traditional Japanese meals for the men, who rented rooms with shared bathrooms.

Having an affordable place to live, where they could eat communal meals they missed from back home, find employment, and speak their language, allowed recent immigrants to build community and get on their feet.

LIVING IN (AND LEAVING) J-FLATS:

By the 1920s and ‘30s, this pocket of East Hollywood was tightly knit and diverse with many Japanese-owned businesses. Much like today, Virgil Avenue was the heart of the neighborhood, but instead of businesses catering to a predominantly Central American population as they do now, you could buy rice and seaweed at Fujiya Market, fix your car at the Endo Brothers garage, get a haircut at Gojobori barbershop, and buy clothing at Torifuchi Dress Co.

Eventually, with the Ozawas’ contribution, a Judo Dojo and Japanese language school opened on Middlebury Street. The Ozawas eventually purchased the neighboring boarding house at 560 N Virgil Avenue as well as a house directly behind their first boarding house where the family lived.

“They were really established in the whole community helping to establish the Japanese immigrants,” explains Joseph Ozawa.

Joseph says the interdependence of the community was critical at a time when discriminatory policies like the 1924 Asian Exclusion Act and the California Alien Land Law of 1913 barred Japanese immigrants from owning property and halted a new wave of immigration. This affected the Ozawas intimately, who had to put their properties in their American-born son’s name, even though he was just a baby.

Federal policies inspired a group of Central Hollywood residents with anti-Japanese sentiments to create an organization called The Hollywood Protective Association, dedicated to keeping Hollywood white. In 1923, B.G. Miller, a local resident, hung a sign on her front porch reading "Japs Keep Moving–This is a White Man's Neighborhood."

By this time, racially restrictive covenants in neighboring Los Feliz and other wealthy, predominantly white areas blocked immigrants and people of color from moving to these neighborhoods.

In 1939, parts of East Hollywood and Silver Lake, including Madison/J-Flats, were given a red grade due to their “heterogeneous” population of Japanese, Black, Jewish, and Latino residents. The Homeowners’ Loan Corporation, a federal lending institution created as part of the New Deal, called this diversity “subversive racial elements.” Redlining meant that the neighborhood was considered risky for investment, making it hard for residents to access home loans, and eventually led to what is known today as the “white flight” of the post-war era. Today, most formerly redlined neighborhoods across the country are undergoing gentrification.

Despite and because of these racist practices, diverse enclaves formed all around Los Angeles. J-Flats was no different.

The area was the kind of place where your neighbor might be Barbara Marshall, whose grandfather, George Washington Albright, was a formerly enslaved Black man from Mississippi who came to Los Angeles in 1892 and homesteaded a piece of land on what is now Westmoreland Avenue. Back then, the neighborhood was all farmland and creeks and you could fish trout for dinner.

It was the kind of place where you might go to the Marshall’s for black eyed peas during the holidays or eat handmade mochi at the Ozawas’ Japanese New Year's feast. Even if the neighbors couldn’t speak the same language, strong bonds formed between families.

“In that generation they couldn’t speak the same language, but they spoke the language of friendship,” says Karen Burch, Albright’s great granddaughter, describing her grandmother’s friendship with her Japanese neighbors.

This interracial solidarity would be crucial for the Ozawas during World War II, when they were forced to leave their home behind for an internment camp.

In 1942, Tsuya and Sukesaka Ozawa along with their two sons George and Joe and their wives Shizuka and Doris and granddaughter Betty, were sent to Heart Mountain, Wyo. where they lived in barracks amongst other incarcerated Japanese Americans. Due to their connections in the community, non-Japanese neighbors ensured their properties were safeguarded while they were away.

“Those people are the reason why those properties still stand,” explains Susan Ozawa Perez, Tsuya and Sukesaka Ozawa’s great-granddaughter. “That’s the story of cross cultural solidarity and community.”

While interned, Doris Ozawa had a baby girl who fell ill amid the harsh conditions of the camp and passed away en route to the hospital. Doris eventually gave birth to another baby, Joseph, who was born three months premature in 1945.

“I was supposed to die but through some miracle I lived,” the now 77-year-old explains. “I was the smallest child to be born in the camp and the only one to survive as a premature child.”

That same year, the family was released and moved back to the community they’d left behind. “His birth marks that era,” describes Susan Ozawa Perez, Joseph’s daughter.

COMING HOME:

Upon their return, the Ozawas’ properties were safe and still owned by them, an uncommon fortune that many other Japanese Americans did not have. Now, the boarding houses took on a pivotal role as the community slowly rebuilt after three years of incarceration. The employment agency at 560 N Virgil Avenue helped many of the men returning from the camps find jobs as gardeners, which was one of the few jobs Japanese men could be hired for after the war, including the Ozawas’ two sons, George and Joe.

By this point, Shizuka and Doris Ozawa, George and Joe’s wives, respectively, ran the boarding houses. Shizuka’s daughter Edith, who was born in 1952, recalls her mother waking up every day at four in the morning to prepare breakfast for the boarders. By the time they went off to work, she’d clean the house, and get ready for dinner. In the evenings, making lunch for the next day was a family affair.

Little Edith remembers packing up sandwiches and rice-based meals for the men who wanted American and Japanese meals, respectively. She wasn’t allowed to go out and play until she had made her contribution to the family business.

“We'd have to sweep the floors and wash the dishes and we'd even be waitresses to serve the food and help cook the food, '' Edith remembers. “It was just all part of our family, to help support the boarding house.”

Edith fondly remembers her time living behind the boarding houses on Commonwealth Avenue. Back then, a fishmonger would drive by to sell his latest catch, and the Helms Bakery truck driver would toot his horn to sell freshly baked goods from little wooden compartments. Her mother, who took care of a large grape vine in the garden out back, would make grape jelly to share with neighbors. Edith’s friends, many who were white, Latino and Black, would come over to play in the large backyard that joined the Ozawas’ properties. Everyone was welcome.

Shizuka became a fixture of the community. Her family describes her as a selfless, generous woman who made sure people were taken care of. They don’t remember her ever evicting anyone, instead opting to work out solutions.

“She was very instrumental in getting people on their feet and helping people out,” says Edith. “I know it's labeled a boarding house, but it was more like a community center. It embraced everyone.”

By the 1970s, Tsyua and Sukesaka Ozawa had both passed away, their grandchildren were now adults and had moved out of the neighborhood looking for better opportunities. The Ozawa family eventually leased the boarding houses to another Japanese family. In 1980, the family officially sold the two properties to a Japanese family who continued operating the boarding houses. By this point a large portion of the Japanese population had moved out as a new wave of Central Americans fled US-backed wars and found community in this pocket of East Hollywood.

Today, those same blocks the Ozawas built a life on are slowly undergoing a different kind of change, but it’s not a new wave of foreign immigrants looking for an affordable place to live and build community in a new country.

Rather, the change is an influx of mostly white wealth in a historically disinvested neighborhood that is leading to yet another form of displacement—this time at the hands of gentrification. Rent controlled apartments are being gutted and renovated for new residents who can pay upwards of $2,000 a month in rent. Old buildings are being demolished and replaced with boxy condos that sell for nearly $1 million. Neighborhood staples like panaderias and dive bars are closing to make way for gourmet bagel shops and natural wine bars. Longtime residents are given cash to leave their homes.

Under these circumstances, Virgil Village is rapidly becoming unrecognizable.

Amidst all this change, the boarding houses and their elderly Japanese tenants stand, fighting for recognition and a safe, affordable place to live.

GENTRIFICATION COMES FOR J-FLATS:

Last year, in February 2021, amidst a raging pandemic, the last Japanese family to own the properties sold both of them to a developer named Matin Mehdizadeh. Upon hearing of this sale, Lindsay Mulcahy, who lives in the house directly behind the boarding houses, the same house that generations of Ozawas lived in, began an application for historic-cultural monument designation.

At the same time, Mulcahy began organizing with the tenants who still lived there, most of whom are elderly and only speak Japanese. Despite communication issues, they formed a Tenants Association and asked the new landlord to address a slew of habitability issues, according to emails sent to Mehdizadeh by Mulcahy on behalf of the tenants.

“When he first took over, he stopped laundry service and stopped cleaning,” explains Mulcahy. “All of a sudden they are living in a construction zone, where it’s harder for them to use different facilities.”

Making A Neighborhood reached out to Mehdizadeh multiple times for comment, but did not hear back.

By May of 2021, Mulcahy had submitted a nomination to the Cultural Heritage Commission on behalf of Hollywood Heritage, a museum and preservation society. In it, she explained that the boarding houses, which served as safe havens for Japanese immigrants both before and after WWII, are connected to waves of Japanese migration and helped establish a community in the neighborhood. They therefore met the first criterion, which recognizes places that are connected to important events of local history and “contributions to the broad cultural, economic or social history of the nation, state, city or community.” “The boarding houses are part of a larger story that helps us understand how our city used to work and how it shapes the place we live in today,” Mulcahy says.

But perhaps most importantly, Mulcahy made sure to also submit the nomination as meeting criterion number two, which recognizes buildings connected to historic personages—in this case the Ozawas, who according to the nomination, were significant in the development of the J-Flats area through their work at the boarding houses, and by helping establish the Judo Dojo and Japanese language school.

The Cultural Heritage Commission voted to move the nomination forward to the Planning and Land Use Committee in October of 2021.

By this point, there were only seven tenants left at the 564 N Virgil boarding house. Many had taken cash for keys offers to leave. 560 N Virgil Avenue was now vacant. The new landlord began renovations on the empty boarding house and on the top floor of 564 N Virgil Avenue, which had been cleared of tenants. According to some of the tenants and their advocates, this construction caused safety issues, with many of them complaining that the dust was making it hard to breathe.

“The new owner immediately started demolishing things,” says Sho Yonaha in Japanese, an 83-year-old tenant and retired gardener who has lived at the boarding house over 30 years. “When I was sleeping, I woke up to the sound of things getting demolished.”

As the weather cooled with the incoming winter months, the heaters in their units stopped working. Bridgid Ryan, who had started meeting with the tenants multiple times a month along with Mulcahy and other concerned neighbors, says the elders would show up to meetings wearing multiple layers of clothing, visibly shivering.

“I had to go out and buy a sleeping bag because it was so cold,” explains James Niimi, an 83-year-old Japanese-American, who has lived at the boarding house for about 40 years.

Mulcahy and her roommate donated space heaters. Los Angeles Tenants Union members donated socks and blankets. Ryan worked with Virgil Normal, a streetwear store up the street from the boarding houses, to donate sweatshirts. “The negligence is really painful and actively harming these elderly guys,” says Mulcahy. “It felt like the stakes got a lot higher because it was dangerous now versus just dirty and irresponsible.”

Niimi, who was born in Hawaii, is the only tenant who speaks English fluently. He moved to Los Angeles right out of high school and worked a variety of odd jobs from painting houses to assembling vinyl records. Living in this boarding house provided a convenient, affordable place to live with people who shared his culture.

“There's not many more boarding houses anymore,” he says. “But the ones that are left like this one here, they bring back memories, and they let people know that there’s been war and prejudice.”

While the nomination awaited a hearing from the Planning and Land Use Committee, a coalition formed to support the tenants. It includes members of J-Town Action and Solidarity (JAS), a grassroots collective based in Little Tokyo, The Little Tokyo Service Center, Mulcahy, and Ryan. Yasue Katsugari of Little Tokyo Service Center and Eri Yamagata from JAS began supporting with translation in the fall. “That was a real turning point,” explains Mulcahy. “It led to a dynamic that felt really generative because there was better connection and better ability to make sure the guys were able to communicate as easily as possible.”

The elderly tenants and coalition members began meeting every Monday amidst the constant construction rubble. In April of 2022, Stephano Medina, a tenants rights lawyer on a postdoctoral fellowship, became the tenants’ pro bono lawyer. “The tenants want to stay and not be homeless, but they also want to live somewhere that’s safe,” explains Medina. “In Los Angeles, working class tenants have to pick whether they want to live somewhere safe or somewhere affordable.”

Currently, the landlord has offered to allow the tenants to move next door, from 564 to 560 N Virgil, to the newly renovated boarding house at the same rent they pay currently, which according to Medina, is unheard of. But many of the men, who’ve dealt with habitability issues for over a year, don’t trust that the landlord will keep his word.

“My wish is to stay here and live as I was living before because I have a couple health issues,” explains Yonaha. “This has been very stressful for me; I just want to live in peace.”

For Mulcahy and JAS, the boarding house not only represents a cultural monument that helps the city understand its history, but it's a reminder of the continual need for affordable housing. Some members of the coalition supporting the tenants proposed the possibility of returning ownership to the Japanese American community in order to convert it into a co-op or community land trust that would protect the tenants and the affordability of the boarding house for future generations.

The organizers are currently trying to balance the immediate material needs of the elderly tenants, while looking at the larger picture of housing needs in Los Angeles. “The boarding house has a history of providing for the community,” explains Yamagata. “We want to make sure the boarding house remains as not only housing, but also as a community facility that provides necessary services. Our role in JAS is to bring the community together and rethink what the ideal kind of housing services the city needs and how the boarding house could be precedent for that.”

After stalling for months, the PLUM committee finally voted to move the nomination forward, along with support from councilmember Mitch O’Farrell, whose district includes East Hollywood.

On June 11th, 2022, over a year after the nomination was submitted, Edith Fukutomi and her daughter, Jennifer sat anxiously in the cavernous chambers of City Hall where the full city council was set to vote on the designation of the boarding houses as cultural monuments. The council members quickly moved through agenda items, and before they knew it, the meeting was over. Confused, Edith asked a nearby police officer if agenda item 11 and 10 had passed. He informed them all items had passed that day. Edith’s eyes immediately welled with tears upon learning that her family’s history and contributions had been officially recognized.“I just feel so proud of my parents and that my family’s history will be remembered,” she said, full of emotion. “I can’t even explain in words how happy and honored I am.”

Although the two boarding houses are now safe from demolition and significant physical change, this means little for the material conditions of the elderly tenants who at this point have been living amidst construction rubble for over a year. But the symbolism did not elude them. And to the organizers fighting alongside them, this recognition helps their cause by bringing attention to the importance of the boarding houses.

“Having the building become a historic-cultural monument doesn't help the tenants’ fight, but it does help the tenants understand the importance of their fight,” explains Eri Yamagata. “The boarding house supported so many people in 100 years of its history, and I think that it’s important to continue to have a place like that in today’s LA, an affordable place where you can get services like meals and jobs.”

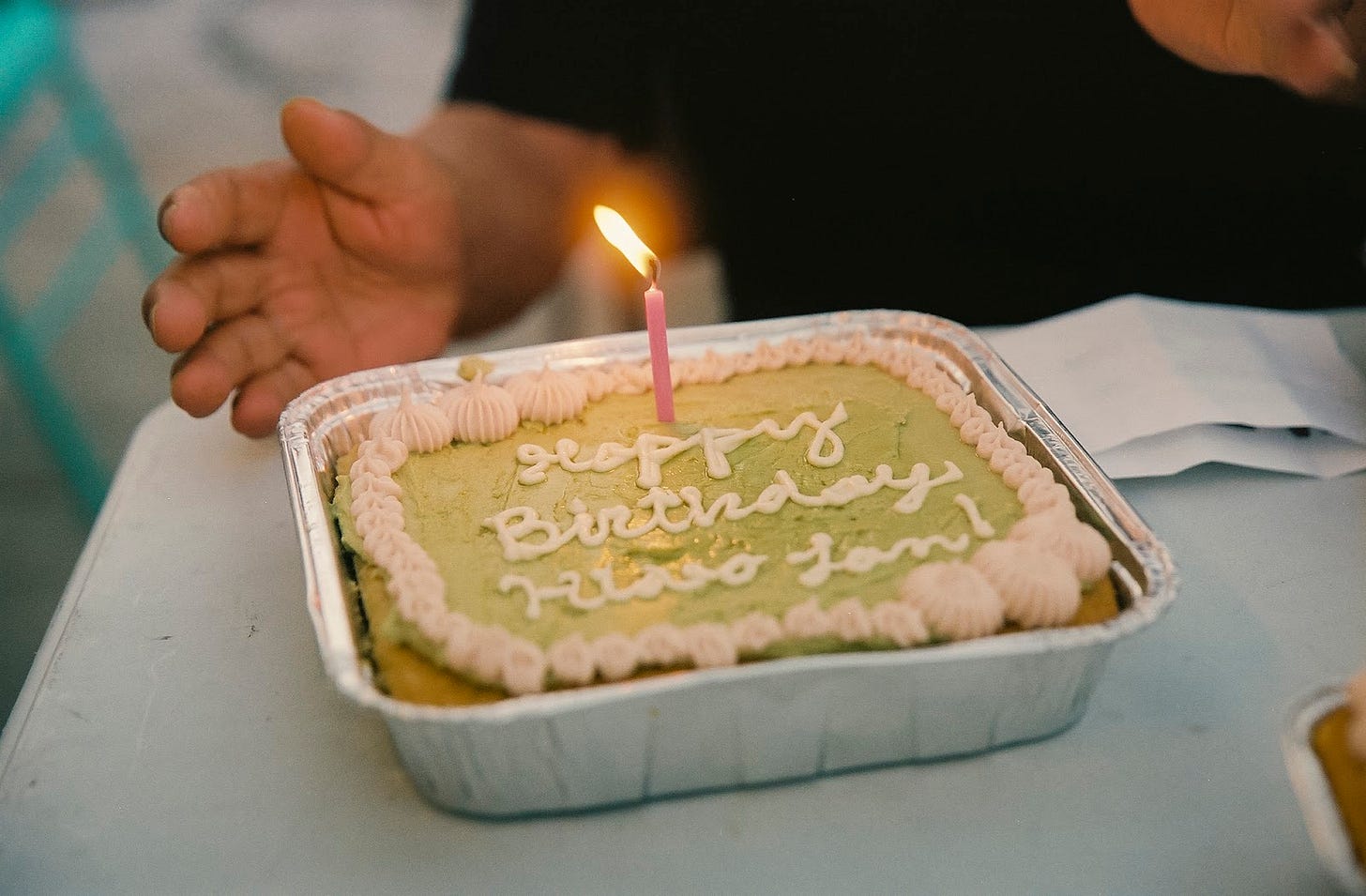

On a recent Monday, the tenants carry chairs into the backyard of the boarding house. As they do every week, they set them up in a circle amidst piles of construction debris and slabs of wood. Yamagata, Ryan, Medina, and Mulcahy, along with other members of JAS, file in, walking past a mound of dirt in the driveway. This time, they have tables, food and homemade cakes to celebrate one of the elder’s birthdays. Medina begins the meeting, explaining the three options the tenants currently have: take cash for keys and leave, move to the newly renovated units next door while paying the same rent, or fight to stay in their current building. He walks the tenants through the pros and cons of each option and answers any questions as Yamagata translates back and forth.

“You can’t trust this guy [the landlord],” exclaims Niimi.

“I agree. I had asked the landlord and he said when you move to the new place it’s $800 but now he’s saying it will stay the same price. I don’t believe it,” says Hideo Suetake, another tenant, in Japanese as Yamagata translates.

Clearly, the tenants don’t trust the landlord.

As the sun sets, the tenants and their advocates fill their plates with Japanese snacks and desserts. A member of JAS lights candles on a cake. They all sing Suetake happy birthday.

“The strongest tool we have is community,” explains Medina. “It sustains us. When we lose community, it becomes so much harder to do this work.”

The future of the tenants is still unclear, but they’re not alone. A community has formed to support them, much like the Ozawas who supported boarding house tenants before them, creating a safe space amidst precarity. This fight is not new.

*Edits:

The original post stated that the two boarding houses on Virgil are the only two still operating as a boarding house, but it’s only the property at 564 that is still in operation as a boarding house.

The original post stated that the Ozawa’s owned multiple properties by the 1920s, but it was by the 1960s.

We added “Los Angeles Tenants Union members donated socks and blankets.”

The story originally states that Shizuka took over day to day operations but it was Shizuka and her sister-in-law Doris.

I work in this neighborhood and have friends who grew up just blocks away. I would have never known about all this history without Making a Neighborhood's reporting. Thank you so much!! Allie