The 'Making A Neighborhood' Exhibit Opens in Wyoming

A new exhibit in collaboration with the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation tells the story of Japanese and Black solidarity in the J-Flats neighborhood of East Hollywood.

Over the last year, I’ve had the honor to work with The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation on an exhibit about the rise of “J-Flats” a Japanese American enclave in East Hollywood located just south of Virgil Village. The exhibit traces the story of the Albright-Marshalls, a Black family who settled the area in 1891, when it was still mainly farmland. Due to discriminatory practices like redlining and racially restrictive covenants, which kept Black and immigrant folks from living elsewhere, this neighborhood, much like Boyle Heights and South Central, became a diverse community. When WWII broke out, most of the Japanese American residents of J-Flats were sent to the Heart Mountain Wyoming incarceration camp. During this time, the Albright-Marshalls, who had developed close friendships with their Japanese neighbors, stepped up and helped safeguard their properties and belongings.

The exhibit, located at the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation’s museum space in Wyoming, and curated by Executive Director Aura Sunada Newlin and myself, is broken up into four walls that trace this history. The first wall explains redlining, racially restrictive covenants, and gentrification. The second wall tells the story of the Albright-Marshalls and their decades long history in the neighborhood. The third wall focuses on the inter-racial solidarity and allyship that existed in the neighborhood and became crucial during Japanese American incarceration. And the fourth wall tells the story of placemaking in the neighborhood across decades, most recently through the rise of a Central American community, and the effects of current gentrification. As part of this section, our efforts with the Making A Neighborhood newsletter are shown as a continuation of ongoing storytelling legacies in the Virgil Village/J-Flats area.

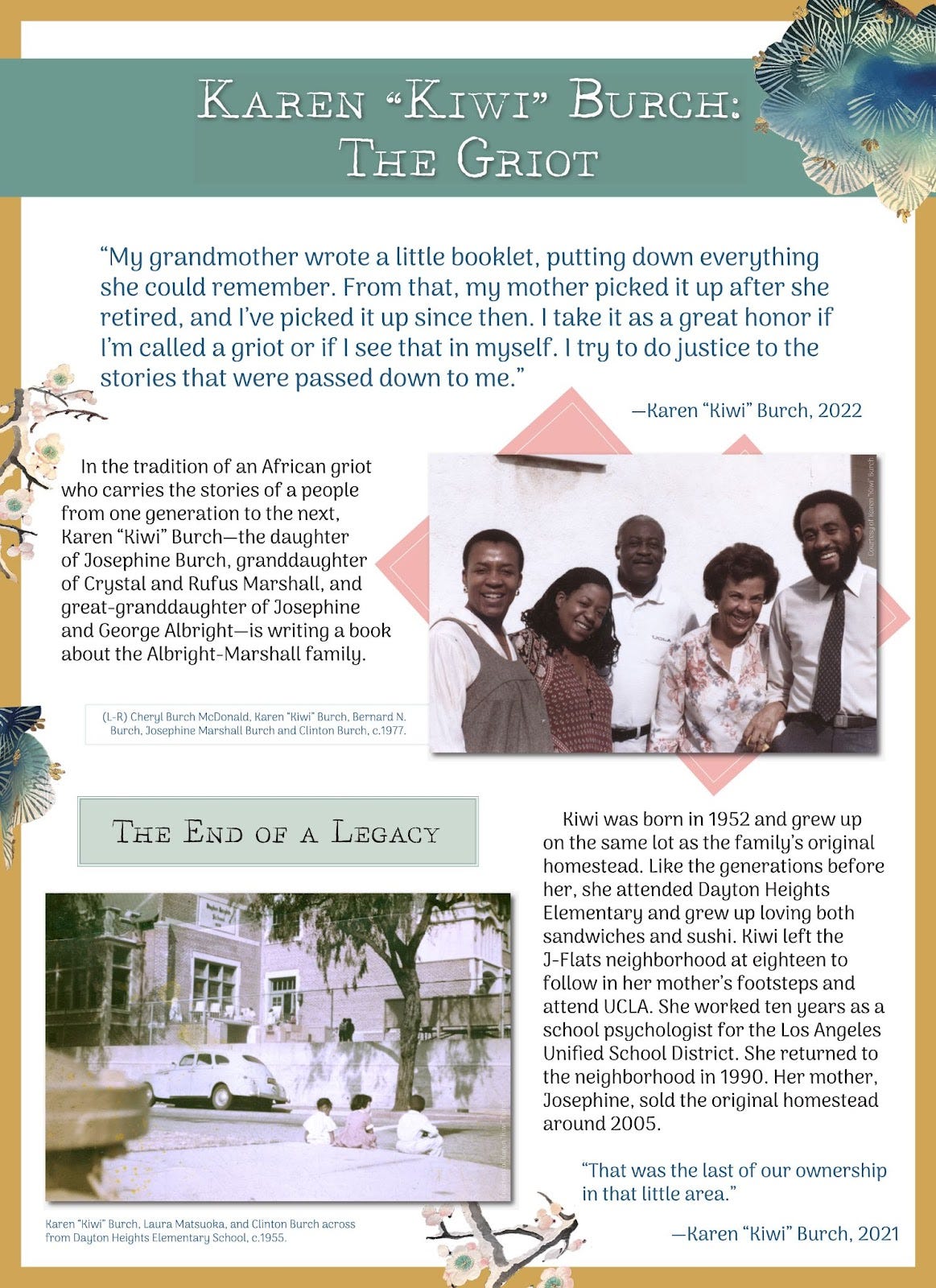

The exhibit opened at the end of July during the foundation’s annual Pilgrimage. I, unfortunately, was not able to make it to Wyoming to physically experience the months-long work we put into this ode to our neighborhood, but members of the Marshall family including Karen “Kiwi” Burch along with her aunt Barbara Marshall, sister Cheryl, and three cousins, Robin, Crystal, and Eric were present to receive the “Ladonna Zall Compassionate Witness Award” for their family’s allyship.

I spoke with Kiwi about her experiences in Heart Mountain. Our conversation below was edited for clarity and length.

Hi Kiwi, to start off can you tell me a little bit about your involvement with this exhibit?

My family, the Albrights, then the Marshalls, then the Burchs, lived in J-Flats, East Hollywood, Virgil Village. We arrived in 1891. You can see that the Albright-Marshall family had kind of developed this area with other families who were early on in the neighborhood. Everybody became like friends and family. I didn’t think about it till I started working with you that they were at the hand of the evilness of white supremacy. Blacks, Japanese, other people of color were going to be redlined into a particular neighborhood. Whites were going to be steered away from those neighborhoods. If you wanted to, generally speaking, build a house in another area and you were a person of color the insurance companies or loan agencies wouldn't accommodate you in your upward mobility.

What were really lemons we saw as lemonade. We love these people, these people love us. The kids all go to school together, this is terrific. The story was about how in WWII, after Pearl Harbor, Japanese on the West Coast were deprived of their civil rights. They were given more days than weeks to pack up and get ready to get on a bus that would take you to a staging area and then later to these concentration camps.

The Marshall family in those few days, did what they could to protect property, people’s homes, their businesses, bank accounts, artifacts of the family that had been passed down through generations.

There was a lot of heartbreak on all sides. Mostly for the Japanese and what they were having to suffer through, but for those left behind too, there was heartache and sadness and loss.

What was your experience like on this pilgrimage? Were there any moments that stood out to you?

I’ve always been [in] the Burch family, especially as the one who never married, but our primary identity in those three days was the Marshall family and what an honor that was. What an understanding for me specifically that this wasn't about me or the work I’ve done over the years, but it was about my grandparents and my great grandparents and what they had done to have a happy ending to this horrible WWII story.

It kept dawning on me, these were the people that were here [incarcerated at Heart Mountain during WWII]. These were the people whose parents and grandparents were here. These were the babies that were born here. And I'm here and this is a very, it’s almost a desolate place. But in that desolation there was spirituality that was palpable. You could feel the anguish, you could feel the sadness, but you could feel that these people were in God's hands.

From my family's perspective, I had heard the stories of taking care of property or power of attorney but not the stories of [the] people in camp. That was all new.

There was a room of reflection with walls made of glass and there were almost like pews to sit on. Wherever you sat you could see out these windows at the Heart Mountain in the distance and this very flat terrain with tall grasses blowing in the wind and this quietness. It was slightly overcast so there was this moodiness. I thought about the evil that had been done there and the suffering that had taken place there and how did these people survive? Here again we’re dealing with survivors. When you look at the African American experience, you’re talking about survivors, when you look at the Native American story of this country, you’re talking about survivors. People who can take a blow and get up and survive. Because the most important thing is to go on. And here it was with the Japanese.

Here are all these groups who are getting together to pay homage, to keep a memory alive and fight what we are still fighting today.

What was it like to experience the exhibit and see your family and neighborhood’s story all the way in Wyoming?

It was so rich, you could go back and look at the pictures, go back and look at the words, and look at the stories. It was rich with history. You got a sense of the people who made up this neighborhood.

I didn't realize how much it all meant until I saw the Kakiba kimono, when I saw the Kakiba kimono in the middle of the exhibit, that’s when it hit me what it meant to have the items protected. To have the property protected. Here is this beautiful kimono and there’s a picture of Mrs Kakiba wearing the kimono in a performance. It all started to blossom as a reality. I could talk about my grandparents protecting the property or looking after a business, but when you see the kimono or when you think about the grocery store or the nursery that survived another 50 years after the war, it’s how one thing leads to another. How one good act can be the seed that sprouts a thousand good acts.

Seeing it there in the context of the exhibit made the whole thing come more to life for me. It became something living. I’m never going to be the same. It was life changing.

It’s so new, this connection between the stories that I heard growing up, the stories that I’ve collected in my adult years of these people and this time, and now this new sensation of being in the middle of the United States in this kind of barren land and having a very concrete understanding of what Heart Mountain means.

Did you learn anything new while visiting the exhibit?

Something I hadn't thought about was that most of the Japanese who came back after the war had to start from scratch. I think very few people had something to come back to. The people that [the] Marshalls [Kiwi’s grandparents] had been friends with were embraced, had businesses to come back to, had homes to come back to, had property to come back to. If you knew my grandparents, and my great grandmother too, it was the kind of things you do for friends. This is unfair, the evilness of our government, and we are going to put weight down on the side of goodness, we are going to help our friends and family.

Since I've gotten back, I’ve heard of stories of people who weren’t so lucky and who came back and their houses were trashed or had been stolen out from under them, the businesses were dead, there was no place for them to live.

I had never thought about it that way because the story connected to my family is when people came back to the neighborhood, they came back to their homes and what was there before. But that might have been more the exception than the rule. That was a startling revelation for me and it made what my grandparents did all the more impactful.

It wasn’t an easy thing they took upon themselves to do but they knew if the shoe were on the other foot that these people would do that for us.

Why do you think it was important to share this story outside of Los Angeles?

We are in a particularly dicey moment in the history of this country and we have to decide which way we’re going to go. This story and this exhibit talks about the allyship of this Black family and these Japanese families. The Black family has a white matriarch [Josephine Albright] so what are we saying about race? I think we are saying it doesn’t matter, that it’s superfluous. It’s the people that came together. It’s the children of the former slave and the school teacher who goes down to the deep south all by herself to help a race of people stand up on their feet after they had been beaten down for so long, children of those two people learn how to be human beings, how to treat your next door neighbor as a human being.

This wasn’t just a story from 70 years ago or 80 years ago. It’s a story that is repeating itself now again with different characters in a different situation. But it’s still repeating itself. We have to keep fighting.

It’s important to tell the story beyond the confines of the neighborhood or Los Angeles or California because there are lessons that touch on the humanity of people doing good to and for each other and people doing ill to and for each other and being able to make a choice about what we do. I think understanding that even in dark times there are good people, there are good people doing good things, that's important to hear. I don't think we can hear it enough.

Over the course of September and October, we are honored to bring you a four-part essay series, written by Karen “Kiwi” Burch herself, about her family’s history and the legacy they’ve left us with despite the fact that none of them remain living in the J-Flats neighborhood.

An inspiring story and well deserved recognition of the Marshall, Albright & Burch family.