Honoring Our Ancestors from Venice to Oaxaca

A Oaxacalifornian shares what Dia de Muertos means to her

Making A Neighborhood is happy to announce a new series called “Neighborhood Dispatches,” which will feature stories, photo essays, poems, and more from neighborhoods beyond East Hollywood. Today’s dispatch comes from Areli Morales Lopez, a bi-national, Zapotec, multilingual freelance multimedia journalist, community documentarian, and cultural worker who grew up in Venice, CA. She covers the Oaxacan diaspora, Zapotec and colonial history, migration, and environmental effects.

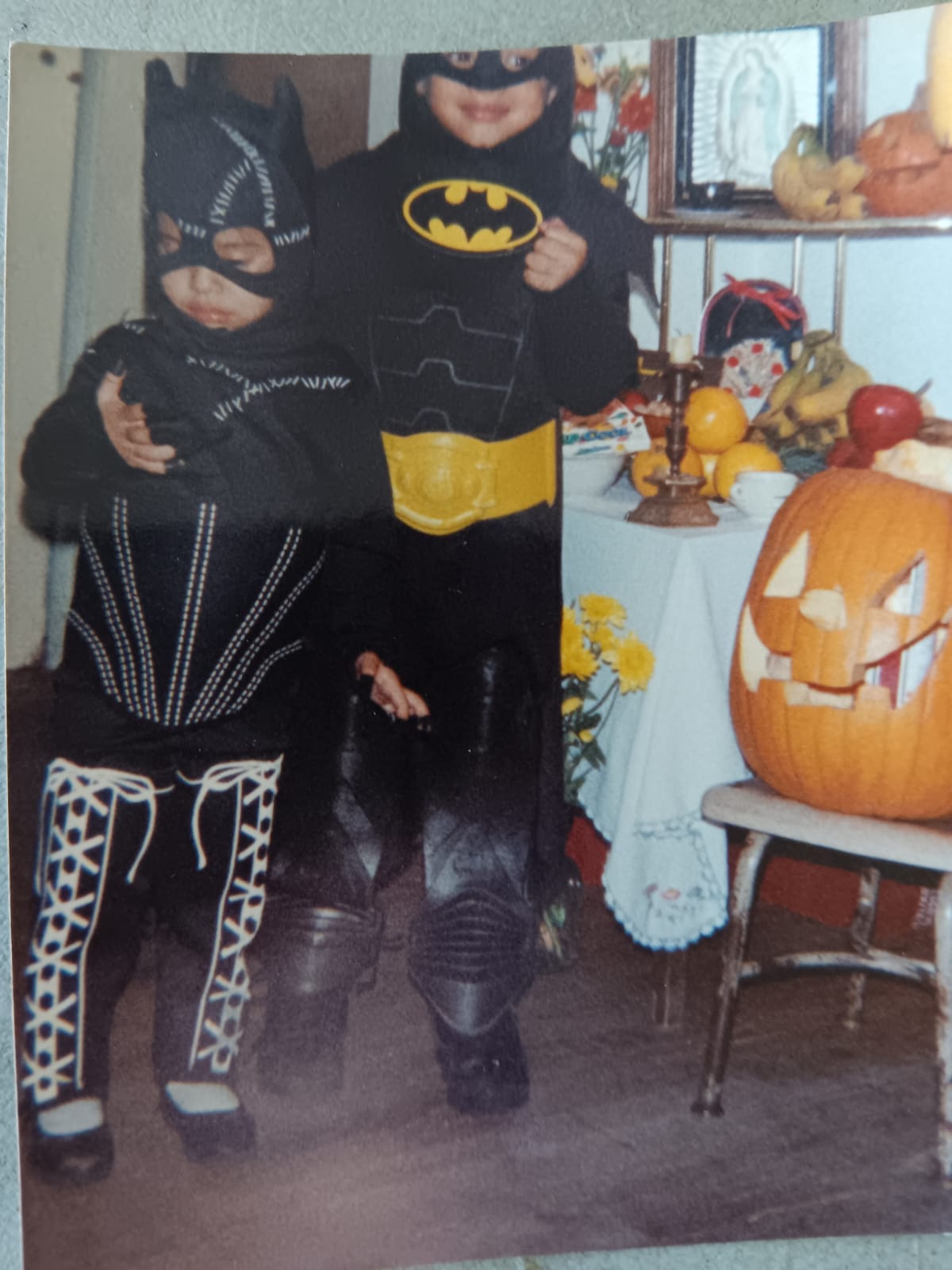

Growing up, during Dia de Muertos, my dad would build the altar in our Venice living room, adding layers of oranges, apples, nuts, candy, and fresh Guava fruit cuttings from our apartment building’s tree. We would spend time at our brother’s Forest Lawn grave, cleaning and decorating it with candy, because he will always be an angelito. Angelitos are those who pass as children, and the belief is they visit on November 1st.

On Halloween, before we could meet up with our cousins to trick or treat, we’d drive the decorated neighborhood streets to Ocean Park in Santa Monica to pick up the pan de muerto we ordered months prior. I remember the warm cinnamon and anise smell that filled the air when you opened the door of Antequera Bakery on Ocean Park Blvd. La Santanera is what our West LA community from Tlacolula, Oaxaca called the bakery, because the woman who owned it was from Santa Ana del Valle, a neighboring village in our homeland. Our region's pan de muerto is oval-shaped, decorated with white piping, multi-colored sprinkles and a carita de muertos—a face made out of flour and food dye that tops the pan. The bread from our Valle is an important part of our offerings and the larger celebration and rituals, which are direct links to our homeland, creating not just memories but roots.

I grew up in Venice and West LA but have had the privilege to also live in my family’s homeland of Tlacolula, Oaxaca for the last 3 years. LA is a second Oaxaca, where our people have been migrating since the 1940’s Bracero programs. The 80’s and 90’s saw the migration wave of entire families like my own. Entire Zapotec villages seem to have settled in Venice and Santa Monica, forming such a deep community that even after mass displacement and gentrification, some pockets still feel like the Californian Tlacolula Valley. Many of us call ourselves “Oaxa-Californians.” The term was popularized as an identity marker by the 2017 exhibit by art collective Tlacolulokos at the LA Central Library. Artists and scholars from Tlacolula gave our bi-national existence visual identity, a sense of pride, and representation.

There are many of us Oaxa-Californians, connected to the generations before us and the culture through these rituals that we share in community with loved ones who we are close to, even if separated by physical realms and borders. Many of our family members are unable to go back or visit home, so they brought the traditions to us with these cultural anchors.

It is said that when a Zapotec person dies, they become the roots that strengthen the culture. This is the Zapotec cosmology, a way of life that we are raised in. Our parents might have not known how to explain but taught us, bringing us up with the education and customs they grew up in, despite the clash of the new urbanity we lived in. In our Dissa Zapotec language, which has as many variants as the Zapotec region of Oaxaca has pueblos, Llii Too Guul (Shi-tu-gul) translates to Dia de los Difuntos Ancestros, the Day of Our Dead Ancestors. In Spanish we call it Muertos, Dia de los Muertos, or Días de Muertos Fieles. This most sacred season is celebrated from October 31 through November 2. During this time, there is a thin veil between this realm and the other, an understanding that we are nature and that as nature our bodies return to the land. There is also an understanding that our souls travel through the nine levels of the Mesoamerican underworld to get to the afterlife, returning to the living world only on these sacred days. Our loved ones are never really gone; we are always connected to them because they are rooted in the land, as well as the immaterial world. During these days, we get the chance to show our respect, tending to them, spending time with them and each other, showing love through offerings. “Ofrenda” in our Zapoteco is Dilli Do’o, which translates to un cariño, an offering, a sign of affection.

Muertos marks the end of the rainy season and time for harvest, where we thank our gods and ancestors for the season and crops. Offerings we place on our altars include corn and seeds from our harvest, to show our dead we are honoring their teachings and caring for the land. These are the important parts of our altars that I am learning and reclaiming in our home in Tlacolula De Matamoros, Oaxaca. This year, in honor of my grandma Ana Maria, generations after her children and grandchildren abandoned the fields for our California life, I worked her land and will offer her my first harvest on her altar, the ultimate sign of cariño and respect. These offerings show our abuelos how their love extends across multiple planes. Filling the altar with flowers specific to our traditions in Tlacolula, we place wild marigolds that grow in our fields, fruits and beeswax candles, all harvest gifts of the land.

Each community and culture has their own death ceremonies and rituals. In Tlacolula, on November 1 through 2, I was taught to visit my padrinos and family and bring a basket full of fruit, pan de muerto, candles, flowers, offerings, and cariño. As we share a meal with the loved ones we visit, we also recount stories that bring the people who passed, who we might have never met physically, to life. Now, as an adult living in my homeland without my parents, I have the privilege and time to learn the Zapotec language, and through that, the deeper meanings of rescuing traditions I couldn't practice in LA. Because my parents can’t physically be here, I represent them with pride and baskets full of offerings, sharing these intimate moments with our extended family. I do this by building up an altar at Grandma's house where my father grew up and bringing ofrendas to our great aunt's house. Here, we drink the Mezcal our late uncle saved for his funeral, which we only drink on these days around his table each year. These moments for just us are treasures that fill me with love and a sense of belonging.

I share the little I know and am learning about our Zapotec way of life and Dia de Muertos rituals to bring understanding and respect. All the themed items and pre-made altares are a commodification that buries the true meaning of the season. Our desire to honor our ancestors and the objects we use to do so are not commodities; they are a testament to beliefs and rituals that have survived countless waves of colonization and migration. I encourage people to channel their appreciation for and wonder about our Indigenous customs to learn about their own familial and ancestral death rituals and beliefs. To honor their loved ones, living and dead, by spending quality time, showing love, cariño, and offerings that are significant to them.

Moreover, if you are visiting Oaxaca or participating in native traditions, here are some points on how to show respect or not be intrusive:

Respect is fundamental in the difference between appreciation and appropriation, and consent is a part of respect. These are sacred times and spaces, so please respect our traditions by only going to homes and spaces where you are invited. Nobody wants tourists at their grandma’s or children's funerals. Treat these days with the respect of funerals. Visiting cemeteries as a tourist is intrusive.

Don’t expect people to be open or to work during these sacred days. Muertos is the most important celebration of the year. People will not work, and my cousin has told me that even when offered three times the pay, most people still won’t work. In the pueblos, most people close shop and are in preparation and celebration.

Support local vendors; buy our bread, flowers and chocolate, but don't expect to visit homes or cemeteries with us unless you have someone to visit. Each pueblo has their own unique flowers and offerings; it's not generic.

Remember that you're on Native land. Many pueblos do not allow exploring and it can be offensive, if not down right illegal, to hike and cut flowers from our mountains. Many towns have traditions threatened by climate change and deforestation; like flowers which only people from the community can get, and each year they have to go further and deeper in the mountains for those flowers. They are endangered.

We do not wear catrina, or skull makeup traditionally in Oaxaca, and our flower crowns are on our altars. There has been some popularity with the makeup in our communities, but it's done like a Halloween costume, which was adopted from our bi-national, globally-connected living. We have our own traditions for dressing up. In my town, the men dress in drag and parade around with mezcal.

If you encounter a muerteada, a parade, and are welcomed to join, bring offerings, including donations to pay for the band and organizers. Don't underestimate how much money these celebrations consume. Some communities and organizers want to keep these events for only the community. Respect that, too. You are not entitled to any of our traditions.

Always ask for consent to take pictures or record. Listen to locals and amplify the voices of the people who live and maintain the culture. Consumption and commodification are usually done without consent. If the intent is to appreciate and empower, then listen and respect. Our relationship to death is beautiful and complex.

How wonderful to read Areli's story, following the series by my sister about our neighborhood in East Hollywood! I lived for many years in Venice, where I raised my children and remember having glimpses of Oaxaca in the area. Later, one of my favorite trips was to Oaxaca, guided by friends with long experience and great respect for the people and the place. I'm very grateful to have this deeper understanding of the people, the rituals, and the history of two more areas that have so enriched my life.

Dear Areli! You are a great and wonderful Teacher. I learned so much about not only the Oaxacanian (sp?) traditions but the traditions that have grown from your lives here in California. I traveled in Oaxaca in 1979 and '80. The beauty and complexity of the culture was evident even then to my young eyes, but you have brought even more layers of understanding to us through your writing. I'm looking forward to the series! Keep Teaching!!